Trending

Let’s talk about one of the most lucrative and widespread forms of online crime. It’s low risk, low effort but with a massive upside. The mark is a roughly $14 billion-per-year industry in Australia. The best part about it? The victims typically don’t even know they’ve been robbed. It’s pretty much the perfect crime.

I’m talking about digital advertising fraud. Those banners across the top of websites, pre-roll videos on YouTube and promoted search results? They pay for a lot of the free internet. Just about every time you click on a link or scroll down an app, a split-second auction between potential advertisers occurs to determine which ad you will be shown. Each ad placement is typically worth somewhere between a fraction of a cent and a few cents, but this very quickly adds (pun really not intended) up. This cash goes back to the owner of the digital real estate, with a cut to the advertising platform owner, such as Google.

Since there’s a nearly endless amount of online advertising space being shown to billions of unique users, and it needs to be sold in an infinitesimally small amount of time, it’s exceedingly difficult to keep track of it all, even if you’re paying for it. Fraudsters exploit this by misleading or outright lying about the advertising they sell and the eyeballs they promise. This information asymmetry is so bad that even the biggest, most legitimate players in this game can be caught out not delivering.

Just last month, The Wall Street Journal covered research by an advertising analytics company that found Google violates its own rules — promising advertisers a premium placement on high-quality websites and only counting advertisements that aren’t skipped — a whopping 80% of the time.

“The firm accused the company of placing ads in small, muted, automatically-played videos off to the side of a page’s main content, on sites that don’t meet Google’s standards for monetisation, among other violations,” wrote the Journal‘s Patience Haggin.

While Google was selling this A+ advertising space — the digital equivalent to being on a billboard in Times Square — fraudsters are using a whole bag of tricks to convince Google that they were actually delivering these advertisements when they weren’t. And it’s the same, more or less, with other advertising platform providers.

Just how big is the fraudster’s bag? Late last month Australia’s peak advertising body IAB Australia released its Digital Ad Fraud handbook that outlined 35 (!) different ways that digital advertisers can be deceived. These include everything from invisible ads (when a digital advertisement is served but a human user can’t see it, perhaps because it’s hidden behind another element on the page) to click farms (humans paid to click on ads to artificially boost the recorded engagement).

The handbook is part of IAB Australia’s way of trying to restore faith in the industry which, up until not so long ago, would “discount or even deny the problem” according to Australian advertising trade publication Mi3’s Andrew Birmingham.

The broader lesson here is that we shouldn’t take the tech industry’s data, statistics and metrics as gospel. Whether it’s the amount of misinformation on a platform (as I wrote about in the last edition of WebCam) or the inflation of view counts that was used to justify Facebook’s infamous pivot to video, big tech is all too happy to play up perceptions of objectivity when it’s using it to spruik its own services. We should always question what is being counted, how it’s counted, and who it benefits when it’s counted that way.

Hyperlinks

The Australian government is making big tech scan your emails, messages

I dug into a largely ignored move by Australia’s online chief which is set to have a seismic impact on how the Australian internet works. (Crikey)

Australia’s eSafety umpire issues legal warning to Twitter amid rise in online hate

And here’s news from another one of the eSafety commissioner’s powers. (Guardian Australia)

Will Albanese’s new ‘misinfo’ law make government the truth police? Not at all

Ironically, there is a lot of misinformation being spread about this law. I dug into what the exposure draft actually says about how it works. (Crikey)

Australian woman shocked to discover her TikToks were being used to advertise Ovira anti-bloating pills without her knowledge

Incredibly, this user was initially banned for creating a TikTok calling out the company for using her story. (ABC)

TikTok is rife with viral Voice to Parliament misinformation

It’s probably not a surprise to most but bears repeating that social media platforms are facilitating the mass spread of bullshit, and they make money off doing so. (Crikey)

Content Corner

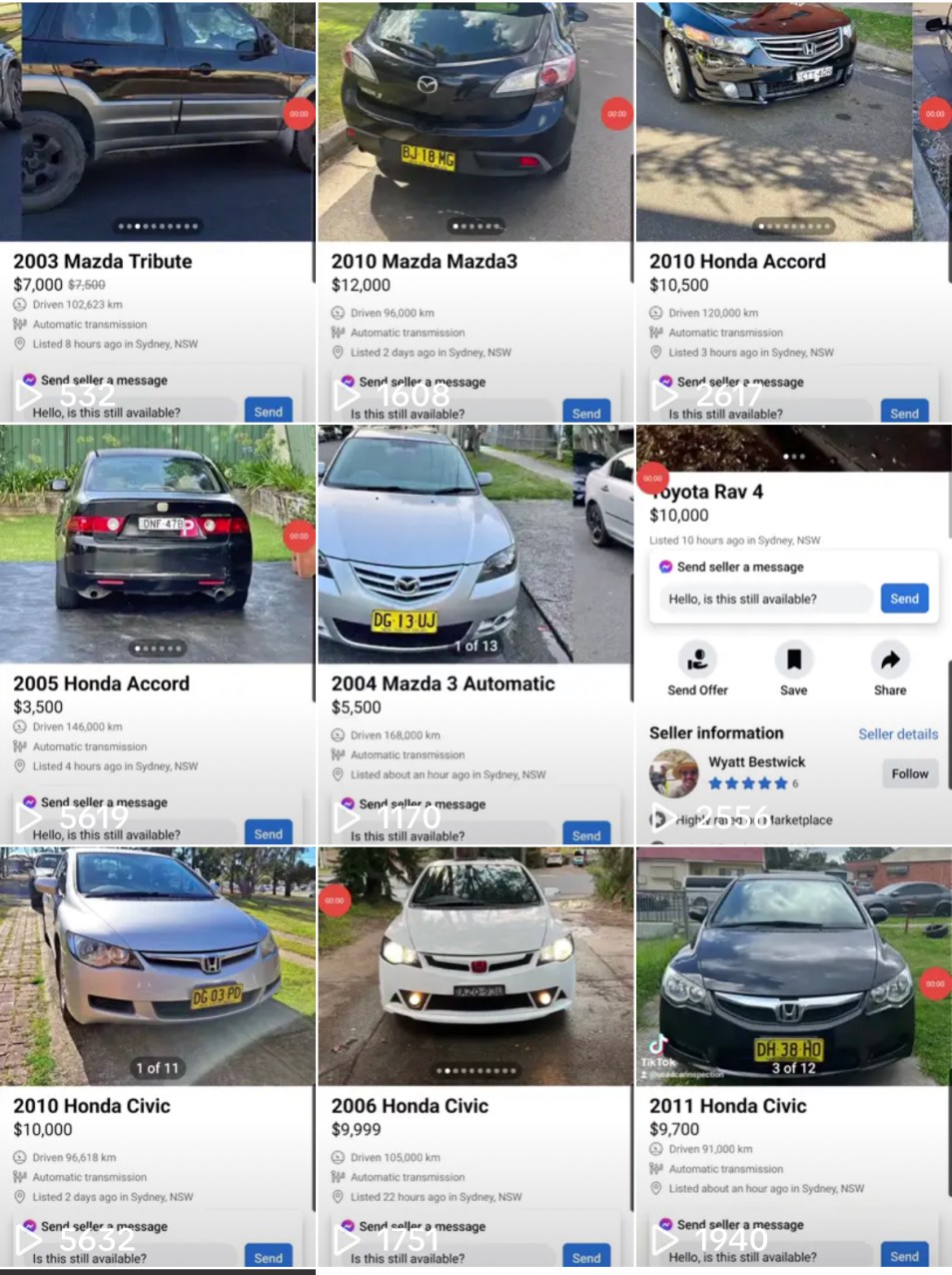

Great news for content lovers! Earlier this month, the NSW government opened access to odometer readings to the public.

Anyone can use the Service NSW app to look up another car’s registration and see what readings they had at their previous three registrations. This will, according to the government, stop unscrupulous sellers from tampering with odometers to make it seem as if it’s done fewer kilometres before selling a vehicle, as buyers will be able to check their odometer history to see if it’s magically decreased.

Why are you reading about this in a newsletter about the Australian internet? Because this move has been a gift to us, the punters who love content. TikTok users are making videos using the information to expose people selling cars with inconsistent odometers on Facebook Marketplace.

In less than a fortnight, a handful of accounts have popped up dedicated to showing examples, like the 2007 Toyota Hilux that suddenly recorded 200,000km six months after registration.

But, in a game of cat and mouse, some sellers have responded by blacking out their number plate details to thwart these odometer checks when posting online.

I’m not a car guy but I found this endlessly entertaining. Everyone loves a good scam and a scammer’s comeuppance. I also believe that one of the great driving forces of the internet is bored people with spare time who want to impress strangers online.

What makes this content — and dare I say, justice — possible is access to the data. It’s like the old saying that “what gets measured gets managed”. When it comes to the internet, any new source of information becomes food for the content machine.

That’s it for WebCam this week! I’ll be back in two weeks, in my new regular slot on Thursday afternoons. In the meantime, you can find more of my writing here. And if you have any tips or story ideas, here are a few ways you can get in touch.

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.