Were you thinking that given the bad odour that surrounds Australian banks, and the now lengthy series of scandals involving the Commonwealth Bank in particular, CBA head Ian Narev would issue a frank mea culpa and acknowledge major and cultural problems at his organisation? Empty your heads of such foolish thoughts.

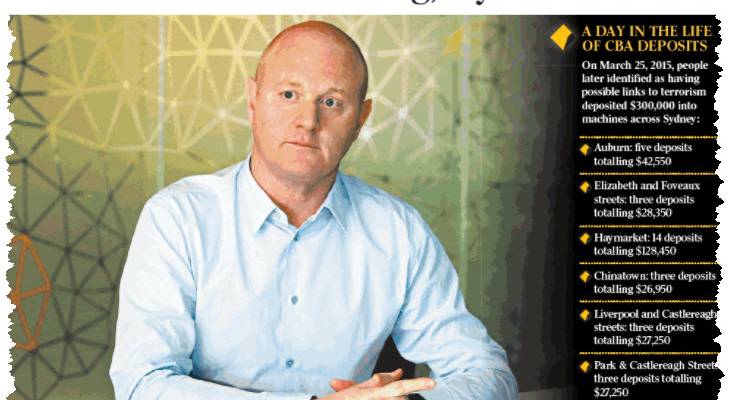

Narev and the CBA board have responded to the money laundering scandal that erupted last week when AUSTRAC took the bank to the Federal Court for tens of thousands of transactions by pretending it’s no biggie. Just a software error, which has long since been fixed.

And it was just one software error — so those 50,000-plus breaches of the law? Well, that means it’s really only ONE breach of the law, so the bank should only cop one fine for that. Of course, Narev generously allowed, it was a mistake, and it needed to be fixed. But it’s certainly not indicative of any cultural problem. “I feel confident in saying that the culture is strong. And I think if you look at the sort of feedback I’ve had from our people on this, you’d probably form a similar view.”

So, relax everyone. Millions of dollars in laundered money, tens of thousands of unreported transactions, drug syndicates disbursing money around Australia and offshore — just another learning moment for the bank. “We will absorb everything that we have learnt that we didn’t know,” Narev assured us. But he’s certainly “not spending any time on thinking about my own position”, as he told The Australian in the other leg of his PR offensive.

All of this is in the context of Wednesday morning, when the CBA will hold a media and analysts’ conference to discuss its 2016-17 annual result, which is widely expected to be a record net profit of around $9.8 billion. One obvious question will be: how much of that profit is from money laundering?

While Narev was peddling his “just one little mistake” line, the Financial Review’s Neil Chenoweth was reporting extraordinarily damaging material from the AUSTRAC statement of claim, which demolishes any attempt to minimise this scandal. Chenoweth provides a blow-by-blow account of how the CBA handled a number of transactions from drug syndicates and other shady entities, which at one stage prompt the Australian Federal Police — having plainly grown tired of sending urgent emails to the bank and not getting a satisfactory response — to raid the CBA.

This gives just a taste of what Chenoweth reports:

“An alert on October 6 [2014], on an account held by Person 33, wasn’t reviewed by the AML team until November 24 when it was referred to AUSTRAC. Another alert on this account was not even reviewed, and while the suspicious activity continued no further alerts were raised. It wasn’t until June 2015 that CBA wrote to the customer seeking identification details. It got no reply so the bank wrote again two months later, and a third time a month after that. The account holder had been in prison since January 2015.”

No wonder the AFP got jack of it and launched a raid in April last year. The nation’s federal law enforcement body had plainly concluded it couldn’t rely on the nation’s largest financial institution to respond to its own internal warnings, let alone the AFP’s. That raid alone should have forced the bank to inform all its regulators — ASIC, APRA and the Reserve Bank — and disclose it to the markets via the ASX.

This isn’t about any old breach of the Corporations Act. Banks are held to a higher standard of governance by regulators than other listed companies because they form the heart of the financial system and the economy. Taxpayers provide an implicit guarantee for the major banks. Deposits up to $250,000 are explicitly protected by taxpayers. Exemplary standards of governance and managerial oversight are to be expected. Banks have to be cleaner than clean. And for that reason, the money laundering charges against the CBA should be the last straw for regulators and the government. Blaming coding errors is simply not good enough.

For something this big, you have to go back to 2004 and the National Australia Bank’s discovery of $360 million of losses from unauthorised trading. At the time, NAB was still recovering from its $4.1 billion Homeside debacle in the US. In the wake of the discovery, the board split, a key independent director was ostracised by the rest of the board, and the Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority and the Reserve Bank impose scores of conditions on the bank, closed its currency options desk and forced it to hold more capital against its assets.

The eventual cost to NAB was $804 million, plus the humiliation of having the board and senior management cleaned out and regulators all but taking control of the NAB’s day-to-day operations for more than 18 months. In its report on the scandal, APRA said “… it can also be attributed to an operating environment characterised by lax and unquestioning oversight by line management; poor adherence to risk management systems and controls; and weaknesses in internal governance procedures.”

What’s the bet CommBank has exactly the same problems? At the very least, Narev and co should get the same treatment that NAB got. And the royal commission should start immediately.

Re Narev’s theory that one software error warrants one fine.

Imagine Narev hurtling along in his car in excess of the legal limit & being picked up by a speed camera. Oblivious, he continues speeding &, further down the track, is clocked by another camera. Two fines are issued – not one.

Someone explain it to him.

Aiding and abetting no longer a crime?

“And the royal commission should start immediately.” Yes indeed!

My business partner appointed his sister to the board of the company that I owned, jointly, with my business partner.

This gave him board control, two Directors to one.

They created a new company bank account which did not allow me access.

“Which Bank” allowed them to create a company bank account that excluded access to one Director, and a Director that was a 40% shareholder?

The Commonwealth Bank of course.

Some commentators are suggesting a complete clean out of upper management and the entire board as just a start. Certainly, no bonuses should be paid to any senior managers who had even the remotest idea or knowledge of this, let alone actual accountability.

But accountability is an odd word, that means only what they want it to mean. Apart form the Royal Commission, I think a huuuuuge fine is in order, something that actually stops them in their tracks.

And yes, I know it is partly my money through my superannuation, but this is more important than that.

Is there any possibility of time in the big house? I wonder if Michael Bradley could enlighten us on just what constitutes criminal activity, as opposed to corporate misadventure.

They shouldn’t get bonuses.

But they will.

And regarding Narev’s salary, surely it is that large because he assumes responsibility for the entire company? And that if he is not held accountable for this his salary is unjustified.