Love Serenade is the best movie made in Australia, a demure and perfectly judged thing that came out in 1996, the tale of two sisters, hairdressers, in a dusty country town in the 1970s. The place has a river for fishing, a row of shops, and a rail line beside and, well, dust, stirred up by the road trains that pass through. The sisters read glossy magazines and listen to the radio as they tighten the perms of the local matronage, dream of escape and eat take-away from the one Chinese place, where you bring your own pots and pans to be filled up.

Into this notime, nospace, the endless stillness of the tiled milk bar, and the dying picture house, comes, to run the local radio station, a DJ, from the city, tall, languorous, saurine. He fills a local house with vinyl sofas, a giant-mounted marlin, caught in another time, and throws out the station’s ancient playlist and brings in the ’70s classics that form the film’s soundtrack, the fat sexy funk of Barry White (“I don’t wanna see no panties”) and Les Crane’s oracular wall-of-sound take on the Desiderata (“you are a child of the universe/no less than the trees and the stars/you have a right to be here”).

The two sisters lay down for him — “would yuh like me to ease yuh loneliness?” — and in the end … well, see the film, I won’t spoil it. A lot went into that movie. As a thumbnail sketch as to why it resonates, I’d say it’s a feminine version of the masculine myth that powered the great films of the Australian new wave, Sunday Too Far Away and such. In doing so, it completes them, without being a neat circle. The girls’ dreams and hopes are not the mere mirror of men’s, neither simpler nor more sophisticated, nor perhaps completable.

Women’s love of men will not make them the women they might want them to be — and yes, I’m talking to you here — and if that happened, the circle would not complete, but simply collapse to a point without dimensions, which seems to be where the current “gender” stuff has got it all wrong. The film unsettles not only itself, like the DJ booming American easy listening across parched wheat fields, but because it rereads the films that went before, gives them an extra dimension. One idea of what Australian cinema was ends there; there is no need to say anything more.

The best scene in that best film is one that barely features the lead players at all. It’s when the Chinese owner of the takeaway relaxes in the ratty back room of his restaurant, and, sprawled on a foetid armchair — this is from memory, I’d prefer to play the film in my head — sings, with guitar, Wichita Lineman, crooning softly that almost not-song, that bare chant, the Rs and Ls commingling:

“I am a rineman for the county

And I ride the county roads

Searching in the sun for another overload …”

Someone in an Australian town in the middle of nowhere, brought there by the dry winds of history, singing American pop, an LA song longing for a place that will only ever hear it on the radio.* That is, as the Cahiers guys used to say, pure cinema, something that could not be done in theatre or the novel, working only by being recorded on celluloid, the thereness of it, the flatness to let the song speak.

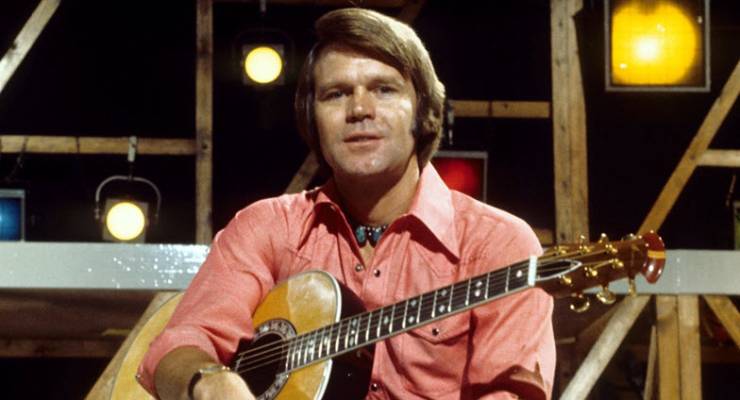

Wichita Lineman, the song about an (electricity) lineman, tracking the faults on the telephone lines, and imagining his love — past? Unrequited? — on the phone (“I hear you singing on the wires”) was by the great Jimmy Webb, who wrote By The Time I Get To Phoenix and Galveston among many others. But it was a hit for Glen Campbell, whose death was announced three weeks ago, and yes, this is possibly the latest obituary for the man who was feted across all media (not least by the great Tony Wright, who constitutes, by himself, about 30% of the reason to still pay for Fairfax). Yes, this is a latebituary, for a man whose death I always thought I’d write about — or use as a hook to hang some writing on — but when it happened, left me stilled and wondering about the point of doing it at all.

Glenn Campbell? Well, he was a session guitarist turned singer, who had a slew of hits in the ’60s and ’70s stuff that everyone, I mean everyone, knew. Wichita Lineman, Phoenix, and Rhinestone Cowboy were just permanently in your head, for about a decade. They were on the radio, they were on the Saturday Show, done by local talent in front of absurd sets of cardboard tumbleweeds and cowboys, they were done by every restaurant duo named something like “Ginger and Apricot” crooning over the claret and prawn cocktail, they were on radio, AM radio, all there was, hits and new entries, and ads for the Eltham Barrel restaurant and intros/outros by Barry Bissell.

Campbell was a great guitarist — his limpid style can definitely be heard amidst the tsunami of guitars in Phil Spector’s “wall of sound” — and he was a great singer, and he, and others around him were great producers, and Webb, Campbell and they created this rich, open, bright sound, indebted to Spector, but less baroque. The songs came at you — “Galveston oh Galveston, I am so afraid of dyin'”, “I know every crack in these dirty sidewalks of Broadway”, ‘and she’ll laugh when she reads the note that says ‘I’m leaving’/ ’cause I’ve left that girl so many times before” — you were in it, away from wherever you were, banging metal at the Repco factory, slinging four ‘n’ twenties in a milk bar, lying on the beach at the back beach, waiting for a wave, and taken away, somewhere else, impossible America, where everything was impossibly bigger and neon.

You want great lives? Campbell had one. Roy Orbison, who wrote six of the greatest songs of the last century, was an ugly little munter, much rejected in love, had about six people he loved die in fires, and died himself aged 52, amphetamine heart, and Campbell just went on and on and on, long after the hits had not kept on coming (prior warning: I will be writing a Mike Nesmith obituary, if he does not outlast me). There’s an old US TV special on YouTube, a tribute to Campbell, with everyone, everyone, from Willie Nelson, to Emmylou Harris and well, everyone, and when Campbell starts a rendition of Crying and everyone slowly joins in, well, if that means anything to you, that means everything to you. It’s the zero point of post-’60s country music, what it was all for.

Glenn Campbell was, if you were in the ’70s, he was just there, there all the time. Those songs were the soundtrack. Before the ’80s, before Olivia and ACDC and Mad Max cracked it, when we were off the side of the world, Glenn Campbell was the image of impossible America, the brio that was going on somewhere else, the life that was being lived. I suspect they felt that as much in Wichita as in Whychiproof, but the feeling of it here was keen, very keen. There were other songs – Tie A Yellow Ribbon Round the Old Oak Tree was one, of 1974, the first year my family started spending a few weeks in summer on the Mornington Peninsula, that seemed to be a hit for six months, playing as we drove down the Nepean Highway, the metal-pressed signs for “Peninsula Bread” along the roadway. It was a song about a bloke on a bus, in transit, that’s probably how it did so well. It burst out of the radio, announcing itself.

Radio. AM radio. Proper radio. Bad radio. No air in it, the levels all flattened. Annoying DJs, annoying ads, and then a song bursting out, like it would blow up the transistor radio you were listening to it on, straining at the tinny speaker. What Campbell and others did to their music was put as much space as they could inside it, and you felt you were inside it, and you were somewhere else.

The high point of this was Campbell’s hit Rhinestone Cowboy, not by Webb. Everyone thinks it’s by Neil Diamond, but it isn’t. It’s by Larry Weiss, and Campbell apparently heard it on tour in Australia, one of whose concerts I think my folks went to in about 1974, and it is, quite possibly, the perfect song, mythical as Blake, tight as Tennyson, doomed as Housman, star culture reflecting on itself:

“I’ve been walking these streets so long

Singing the same old song

I know every crack in these dirty sidewalks of Broadway …”

Well, hell you know it. You’ve roared it out at some time. But it wouldn’t work without the orchestra, the studio, the production, the space, the voice, and that was all Campbell, in whole or part. Looking back at the original video clip — which consisted of Campbell awkwardly riding a golden palomino round a rodeo ring, lifting a Stetson occasionally — I realise that the song only came out in 1975. So I was hearing it for the first time, the first time. I’d thought it had been round already forever. It seems unimaginable that it has ever not existed.

But that’s the point isn’t it? From here on, I could write one of these obits a week, as the heroic figures of the boomers and gen X — a generational Hitler/Stalin pact against the Millennials — go to dust. Because there’s so many of them. Because before about the mid-1960s, pop culture was one new record a week, and the movies changing at the Bijou, and after that there was so much, so much. And now everyone who did it is dying. And what came after is a culture more fragmented and thus less sentimental, for worse and better. So we mourn the heroes of a postwar mass culture, but in doing so we also mourn mourning, because it will not be done this way soon.

That is why, that is one reason why, I have resisted the obituary form of late. Because, OK, boomer/gen X culture is dying, so what? This one goes, that one goes, who gives a shit? But at the same time, there is no better occasion to preserve a living situation than through a dead one, and to remember, through Glen Campbell, a time when my parents were happy and prosperous from their efforts, and went down the Nepean of a hot Friday summer evening singing, to AM radio, Rhinestone Cowboy, Sweet Caroline, the Carpenters’ Superstar, and Wichita Lineman, barely a song, loose-limbed, as simple as, recorded by the ethnographers, the work chants on the Nile Delta, which may be, in one form or another, more than 6000 years old — “and I need you more than want you/and I want you for all time …”

God, AM radio. AM radio was God. There was nothing else. The likely hits were pumped out of 3XY, 3MP, the greater 3UZ nine-three-oh, and etc. They became actual hits because you bought the singles. Singles! Plastic circles, which lasted four minutes! They sold in their millions! There was something you were seeking in them. I recall, going down the Nepean one summer, to Morny, Rye, near Rosebud, we stayed in this big house, multiple hirings, and there was a girl there, Cathy, 20 years old. Even at nine years old, I could see she was hot as summer asphalt, had lanky, long-haired boys back to her room, played Monopoly with me, broke off when more boys came round. And she loved AM radio. She’d shush you if a song she liked came on — something arty by the Steve Miller Band, homegrown cool like Sherbert, or a first-half-seventies one-off, like Seasons In The Sun a Rod McKuen translation of a Jacques Brel, which made her weep, in her dot-painting patterned bikini. The Morny was besieged with goannas in those days, I wonder if it still is. They’d peep their blue-leathered phallic heads out of rock holes, Cathy would squeal, I’d swat them away, the hero. They’d withdraw slowly, shaking their heads, more in sorrow than in anger. Three weeks in, she met some lanky surfer guy, and we barely saw her for the rest of the summer. But the music kept on bursting through the tinny speakers: walking these streets so long; Billy, don’t be a hero; like ships in the night; some people call me the space cowboy …

***

Well, that was mass culture, that was what what it was. In Australia, from about 1965 to about 2000, when everyone was on the same page. Its heyday? About 1970 to 1995, one generation, festooned with “dissident” alternative. The reluctance to write an obit for whatever boomer/gen X star had died that week? The sheer multiplicity of them, the weekly dying, the this or that minor departure. The sense you were dying with them. But the sense also, that as boomer/gen X culture died, mass culture was dying with them. That was, in some way, a liberation. And above all, the singular experience for Australia: that as part of its popular culture, we know it not, and take the imaginary as the real. We are thus more privileged than those for whom it was an omnipresent. I’ve been to Wichita. It’s nothing like the song. America is nothing like the song.

Campbell never had a big hit after the ’80s, though he kept turning stuff out, and touring, and his extraordinary fluid, limpid lead guitar became an ever-greater part of the act. Wichita wasn’t Wichita, and Australia wasn’t really the dusty no-place of Love Serenade, which traces its lineage back as much to Australian Gothic, that persistent genre from Wake in Fright to now, the sense that our very presence here is grotesque in some way. Our nostalgia, our loss, our fondness, now is for limits — the one Chinese takeaway, the one No. 1 hit song, a holiday as a couple of weeks’ rental of a fibro house near the pier — as everything becomes possible, and nothing actual. And there’s no real way to end a piece like this; these sorts of obituaries are little more than “thank you” letters to people who can’t read them. That’s my love serenade. And as the songs did, and AM radio itself did, slow faaaaaade …

*at least that’s how I remember the scene. I decided not to rewatch the film; it plays perfectly in my mind

Sorry to see his passing.Sorry for the loss to family….he had a good innings.

Can we get a think tank to gether to get the ecomomy on a move forward.People like simon crean who speaks now with a conservative tongue.And that bloke that left his shower bag in a hookers shower….a good polly otherwise,a good brain.We have bush and ground that needs water taken to it interstae,lets get moving.Surely we can get people here on visa,s if we can,t get those of invalid pensions and the dole into the work force.

Many of the countries achievers are never thanked for coming,less your a journo

You stirred up some rich memories with this piece, Guy. Some of us are fortunate to have lived in that era of great popular music. It was tuneful. What ever happened to tuneful…

Incidentally, Sergio Mendes & Brazil ’66 managed a fine version of ‘Wichita Lineman’.

I remember the impression that movie made- the feeling it gave me. I don’t remember the details and I don’t want to rewatch it, either. Memory’s enough.

You made me cry, Guy. In public. Thank you.

That is one of the most beautiful pieces of writing I have ever read. I am another in my late forties who was deeply affected by Love Serenade when it came out, it’s soundtrack and rediscovering “Witchita Lineman”, “Desiderata” “Rockin’ Chair” and a whole lot of AM radio classics from my childhood. I recently watched the doco “I’ll Be Me” which showed Campbell on his final tour as he slipped further into the clutches of dementia. But his guitar playing and voice remained beautiful.

Thanks for that because all I could muster was “Wow and that extrodinary piece of writing deserved better

Such tender beautiful writing. Such an open generous sensibility, too. Most metropolitan artists are tone deaf to the Oz country but Love Serenade gets it achingly right, as does this languid expansion-riff on it. Just extraordinary, weaving such unlikely, incongruous threads into a universal. Rhinestone Cowboy/Wake In Fright…hell of an aesthetic leap there. Unless you grew up in a tinsy citrus hamlet about sixty miles up the Murray from Robinvale/Sunray (the LS setting), casting about for anything to slake an inarticulable thirst for escape/transcendence. As a 10, 11, 12 year old I used to lie in bed in the sleep-out and listen to Beach Boys on a crappy Casio tape deck through a home-made ‘stereo’ earpiece. Wall enough of sound for me…Campbell was Wrecking Crew, his guitar was all over Brian Wilson’s Surfari/Pet Sounds transitional phase, perfect pop songs of adolescent yearning…I Can Hear Music, Don’t Worry Baby, When I Grow Up To Be a Man, God Only Knows (of course)…four hundred miles from the nearest decent break and I had no more of clue about what a Prom was than a Lineman. But it all hits the same spot. Somewhere there’s the perfect girl, at the perfect party, in the perfect placeand time, and she’s waiting just for…you. Good to see Superstar get a run, too. What a voice that Carpenter girl had.

Such a treat when GR writes about the scrub like this. Makes up for all the mean things he says about Barnaby. Ta.