“This will be a thoroughly Liberal Government. It will be a thoroughly Liberal Government committed to freedom, the individual and the market.”

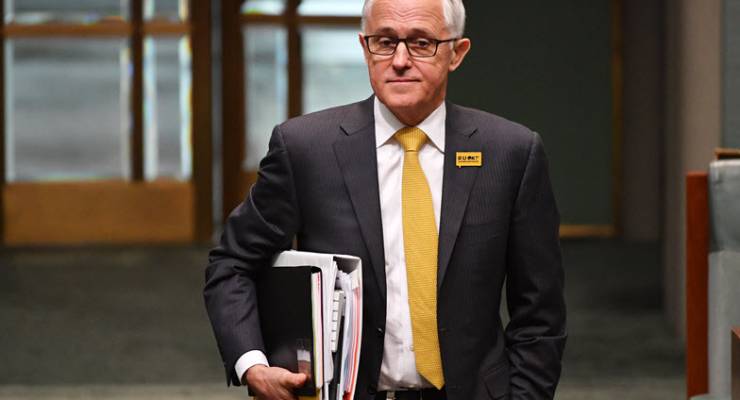

How long ago 14 September 2015 seems, and what a different world. Pre-Trump, pre-Brexit, pre-Hanson, at a time when the verities of the Age of Neoliberalism seemed eternal. Malcolm Turnbull’s promise the night he became Prime Minister to lead a “thoroughly Liberal government” (the capitalisation was his own) was rapidly broken, and not at all because of some negligence or malice on Turnbull’s part, but because the world in which his commitment was made was rapidly ending. “The hour is late,” he said more than once that night, and he was right in ways that he couldn’t possibly know.

But reflect on those words. Freedom. The individual. The market. Turnbull offered a kinder, gentler neoliberalism — not in an economic sense; if anything, he was (initially) all about embracing change and disruption, and the early focus from new Treasurer Scott Morrison was on the spending problem he had inherited from Tony Abbott and Joe Hockey. But in a social sense: gone would be Tony Abbott’s strident social conservatism and his bitted hatred of modernity, replaced with a genuine commitment to the social logic of individualism, the liberalism that Turnbull had always espoused, that saw him long ago embrace marriage equality, republicanism, that saw him take his cue from Margaret Thatcher on climate action. The government Turnbull would lead would be the iron fist of the market enclosed in the leather jacket of Q&A Malcolm.

Two years later, the insults and abuse fly in a marriage equality postal survey imposed on him by party reactionaries (Turnbull having eloquently demolished both postal surveys and plebiscites in times past), the deficit is still $30 billion, government intervention is de rigueur and Turnbull spruiks the virtues of coal-fired power.

Turnbull hasn’t merely been trapped by the far right of his own party– the equality and climate denialists — and his inability to assert his authority; he’s been wrongfooted by the unexpectedly quick death of neoliberalism and the populist resentment that has driven it across the west. This has frequently made for an ill fit for Turnbull — one day assailing Bill Shorten as a Corbyn-style socialist threat, the next day lambasting Shorten’s business links while himself engaging in a de facto nationalisation of power plants and gas supplies. Nor is Turnbull at all consistent: he has embraced big-government interventionism not merely on power but on manufacturing, via the defence budget and an ever-more aggressive anti-dumping regime, while spruiking a tax cut for the world’s biggest corporations, trying to slash higher education funding and increase student debt and urging wage cuts for low income earners.

No government is ever ideologically pure, of course, and the best governments are marked by pragmatism, but Turnbull’s government is more accurately described as deeply confused than pragmatic. Not merely is it crippled by a divide between conservatives and liberals (imagine the media coverage if a Labor government by its own acknowledgment couldn’t devise an energy policy because the Left was holding it hostage?), but it is intellectually divided in its own view of the world. Is it 2015, when the market was still something to be celebrated, or 2017, when corporations are regarded with seething hatred by voters? Is it the age before Trump and Brexit, or is it the era of staggering incompetence in the White House and Number 10?

At no stage has Turnbull sought to try to address the electorate’s disaffection for market economics; neither he nor his Treasurer have ever attempted to explain to, to educate, voters about the virtues of markets. And, contrary to the views of business leaders who still think all a return to neoliberalism requires is some 80s-style “leadership”, it would have been a fool’s errand, because it’s not the 1980s, and Turnbull is certainly no Paul Keating. The electorate has a pretty solid understanding of the market, thank you very much, because they see it in their stagnant wages and their soaring power bills and in the media week after week as ever more corporate scandals erupt out of the business pages and onto the front page. Any politician looking to “explain” the virtues of neoliberalism to voters would be lucky to escape tarring and feathering, or at least the social media version thereof.

Turnbull is thus stuck with the question “what comes next?” If we retreat from neoliberalism, where do we go? Back to a Keynesian past of interventionism? Back to an era fondly remembered for full employment that masked a dramatically lower participation rate, the economic disempowerment of women and an uncompetitive economy? After two years, it’s not clear that Turnbull understands that this question needs a coherent answer rather than the apparently arbitrary policy positioning that has marked his time in government.

Malcolm doesn’t seem to actually have a “way”. He seems to be content to be the front man for a failing and flailing hard right Government. Like the barrister he is, he is happy to take instructions from masters he may or may not respect, putting their case, no matter how harmful or absurd it might be. The fake ‘plebiscite’ and what passes for an energy and climate policy in this Government are just two of the more egregious examples.

What a load of apologetic blather.

Turnbull is a long time member and current leader, just the first among equals more or less, of a far right capitalist religious reactionary socially conservative party that far from being ‘confused’ has successfully carried out policies that are well and truly in line with the ideology it has espoused for several decades.

There is nothing new from this mob.

The environment, women, minority groups, workers [unionists in particular] the unemployed – anybody that does not fit into the club of rich white religious men – have all suffered from the current policies and practices that have been continued seamlessly all my life of 70 plus years.

So can we please stop with the “Mal could be great if only …” excusing.

It’s become well and truly boring.

Thanks McDuff, I tugs me forelock.

A brainiac “business genius” who couldn’t wait a few months (for Abbott to self-immolate the Limited News Party), walk in and take over the steering of the Opposition sans nuts and bolt barnacles, to wait a term (maybe two) for Shorten to short circuit. No, Malpractice had to have a drive of the Keystone Cops fire engine “NOW!”.

Then – to compound interest – calls a DD election (to clean out the stables) : where only half a quota gets Hanson’s litter into the mews upstairs?

Then there’s that optional “veracity to keep power”?

… Ever seen BSE at work?

Th BSE was probably caused by the much too close association with the scabies infected sheep who is DPM.

‘Back to an era fondly remembered for full employment that masked a dramatically lower participation rate, the economic disempowerment of women…’

Bernard, what do you mean by ‘masked’ here? The female participation rate rose most rapidly in the 1960s. The end of full employment in the mid-1970s stalled the rise of the female participation rate for a decade, and started a long downward trend in the male participation rate (which eventually stabilised but never reversed).

If you mean that full employment was only possible in the first place because of low female participation, so that wishing for full employment is sexist, what exactly is the argument? The unemployment rate is the ratio of unemployed to labour force, so you can in principle have full employment at any participation rate. (Of course if a lot of people suddenly enter the labour force it would take a while to absorb them, but the timing and pace of women entering the labour force is way off for that to be an explanation of what happened to full employment in Australia.)

Michael…what happened to full employment in Australia is, first and foremost, multi-faceted. Having said that, it has become a lot worse since we have had ‘open slather’ on various types of immigration to satisfy the ever demanding corporations. This is just a pathway to creating a pool of workers so that further down the track…if not already…said corporations can offer lower wages, and in some cases (‘interns’) another method of slavery.

We are going nowhere until this basic fact is recognised…and we drastically reduce immigration levels for a few years to allow employment to ‘catch up’. That way the current populace will have a chance to educate/train themselves for the jobs of the future and negotiate for a liveable wage. Maybe then inequality will reduce to manageable levels.

Of course, I absolutely disagree with Bernard’s spiel on poor Truffles…if you can’t stand the heat, get out of the kitchen…and take your toxic government members with you!

REVOLUTION NOW!!

It would indeed take nothing short of a revolution to alter immigration/population levels when faced with bi-partisan political support,corporate vested interests and procreating god botherers. Not to mention the ongoing increase in numbers of refugees generated by war and the effects of climate change.

I hope I’m wrong but it seems that the horse has bolted/the genie is out of the bottle and it’s too late to turn back the tide.

Turnbull is stuck in no mans land, he can`t go forward

and he can`t go back, and he can`t stay were he is, so he`s stuffed, hoist by his own petard, he had the good grace of the voters and thereby the power to control the party but lacked the courage or foresight to capitalise on it, he bought the party but couldn’t control the mad right so Abbott has put him to the sword , he will go out in virtual disgrace and could even do a Howard and lose his seat, he has no body but himself to blame, if he had any spine or credibility left he would call an election and make the neo cons face the music. at the polls