The most watched series in the history of ABC iView is Bluey — a new Aussie kids’ show focusing on a family of blue heelers. Since its debut in October 2018, Bluey has generated 21.3 million views (and counting). The show was also 2018’s number one Australian children’s series on broadcast television, with an average audience of 341,000 (metropolitan and regional).

The closest rival is Peppa Pig, which has a similar draw but hundreds of episodes and a longer lifespan; Bluey has just 26 episodes to date. It’s still a pup in the television landscape. So, where is this enormous success coming from? And is it indicative of a larger boom in Australian kids’ content?

Love for local stories

“Half of all visits to iView are for children’s content,” ABC children’s television manager Luka Skandle tells Crikey. “Popular adults’ programs such as Mystery Road and Killing Eve also receive high viewing numbers on iView — but with significantly less repeat viewing and longer episodes.”

According to the ABC’s 2017-2018 annual report, iView had 57 million program plays per month. And, according to Skandle, Australian-made shows tend to outperform series from overseas. There are big international children’s television brands from major production houses with millions of dollars behind them that are big drawcards for our audiences… But shows such as Bluey outperform them all, thanks to its sheer relatability and its brilliant stories and characters.”

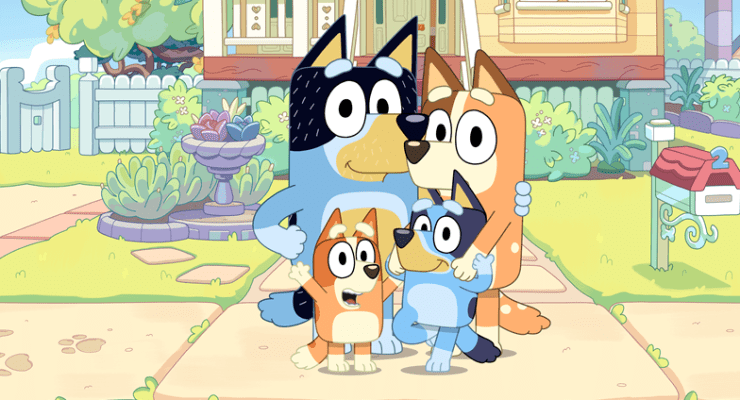

Bluey is made by Ludo Studio, a Brisbane-based creative studio, and is inspired by the family life of its writer and creator, Joe Brumm. Each seven-minute episode focuses on a family of blue heelers: Mum (Melanie Zanetti), Dad (Dave McCormack), little sister Bingo, and big sister Bluey. They go to the beach, host family barbecues, wait for takeaway and visit local markets; an endearing slice of Australian family life.

“Another example is our school-aged hit Little Lunch, which enjoyed unprecedented success among its target demographic for the same reasons — telling authentically Australian stories that are well made,” Skandle says.

The drama over kids’ drama

However, CEO of the Australian Children’s Television Foundation (ACTF) Jenny Buckland says the success of these locally-made shows is not driving an investment in more kids’ programming.

“Broadcasters and screen funding agencies have finite levels of funds, and it is fair to say (and our submission to the Senate inquiry demonstrates) that they prioritise adult content over children’s content: children’s content gets the scraps basically,” says Buckland.

“The funding that the ACTF receives from the Commonwealth is a tiny portion of the overall funding envelope — at $2.85 million — and it has stayed at that level for years.”

There’s also an ongoing debate about what proportion of this funding should be given to “drama” projects, and what that genre distinction actually means. In a 2017 report in The Conversation, Anna Potter and Huw Walmsley-Evans noted:

In recent years there’s been a dismaying lack of new live-action shows, or recognisably Australian content. Instead, local children’s TV has become dominated by animation with little sense of place.

While Bluey has a strong sense of its Australian roots, there are several animated co-productions that qualify as “Australian content” despite not originating in Australia or looking/sounding particularly Australian (Vic the Viking, Sea Princesses, and a series created by pop singer Gwen Stefani called Kuu Kuu Harajuku to name a few).

Commercial broadcasters in Australia each must screen 96 hours of first-release Australian children’s drama every three years — an average of 32 hours per year. Under this rule: animation counts as drama. And, due to this model, live-action drama and animation that’s distinctively Australian — where most of the work, writing and voices are done in Australia — is slowly disappearing.

According to Screen Australia’s Drama Report 2017/18:

10 children’s dramas entered production in 2017/18 generating 71 hours of content (five-year average 109 hours), with a local spend of $49 million (five-year average of $56 million).

The decline in spending and hours of content over five years is noted in the report as due to:

Low official co-production activity with only one title produced, a decrease in the number of animated productions (which tend to generate a greater volume of content than live action titles), and the cyclical influence of the children’s content quotas on commercial free-to-air broadcasters.

A spokesperson from Screen Australia told Crikey that “Screen Australia is already committed to investing in children’s television content and will continue to do so. We’re excited for Bluey to reach international audiences. Children’s television already has a history of generating substantial sales overseas.”

Screen Australia notes five dramas (Mako Mermaids, Nowhere Boys, H20 Just Add Water, Little Lunch, Dance Academy) have already notched up international sales worth nearly $14.4 million. Four new children’s shows are also set to debut in 2019 with Screen Australia’s support including The InBESTigators, Hardball, The Unlisted and The Strange Chores. Beyond 2019, Screen Australia has also invested in children’s animation including Little J & Big Cuz, 100% Wolf, Spongo Fuzz and Jalapena.

These are locally-made shows with huge audiences; there’s clearly a demand for more.

Fighting over the scraps

Buckland is optimistic about this local content, but has little faith in funding options.

“The ACTF has actually spent record levels on script development investment over the last couple of years so we know, first hand, that Australian producers and writers are working on a lot of great program ideas. But the sad thing is that they won’t all get financed, because it’s really hard to get them made with the level of funding available to children’s content via the broadcasters and Screen Australia.”

“If we don’t make sure there’s Australian content on streaming services, children’s access to Australian stories will be diluted … without some kind of system that encourages the streaming services to have Australian content we’ve got no guarantees that it will continue.

“It’s important for everyone to see their own stories reflected back at them because it contributes to our sense of self and national identity, but it matters to children most of all.”

Bluey has set an incredible precedent, but the industry arguably isn’t equipped to meet the demand of a generation who know how to operate a tablet or smartphone before their second birthday. If only the industry was as healthy as the viewing numbers.

Part, at least, of the reason kid’s shows get more iview views is that kids are happy to watch the same show again and again.

Gods yes.

Until I had a little niece old enough to demand to watch the same Wiggles DVD over and over and over and over and over again, I didn’t really realise that- when I was a kid, you mostly had to watch what was on the telly, which for kids was mostly first-run eps of Sesame Street, Play School etc. Rewatching wasn’t really on the table.

What a heartening story – makes me wish I had a TV or knew what iView is.