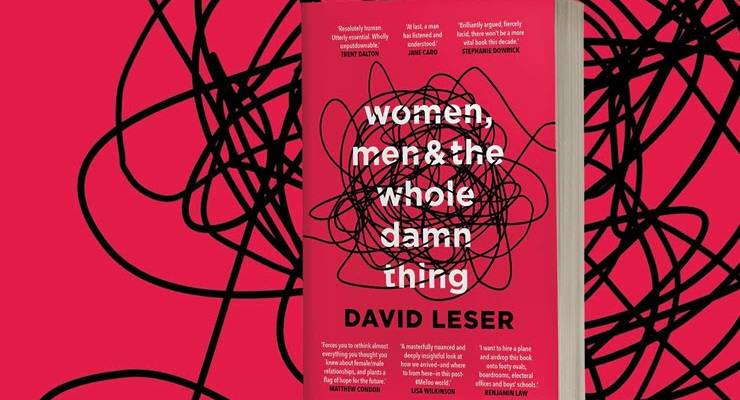

In February of last year, Good Weekend devoted 7000 words to the Me Too movement in an article titled “Women, men and the whole damn thing”. For the task of covering one of the biggest social moments in women’s history, the magazine appointed a man: journalist David Leser.

I remember reading half of the article the weekend it came out, confused and a little pissed off, before throwing it away unfinished. At a time when other publications were handing the mic to survivors and taking down abusers, it was a puzzling choice for a magazine of Good Weekend’s stature to instead get a cisgendered man to rehash what had already happened almost six months after everyone else.

I wasn’t the only one rubbed the wrong way by Leser’s article, or the subsequent news that he’d nabbed a deal with Allen & Unwin to expand the piece into a book. Columnist Van Badham described the fact a man was covering this intimately female fight as “precisely the structural sexism that Me Too has illuminated”; Nikki Gemmel called it another way for men to drown out women’s voices; The Guardian asked if men have the right to cover the topic at all.

Leser is well aware many will think he’s not qualified for this job. “I am a straight, white, middle class male who has breathed the untroubled air of privilege all my life,” the very first line of the book disclaims. He goes on to front up to the ways in which he’s an imperfect man: he let his ex-wife pick up the bulk of the domestic labour during their marriage, he was unfaithful, he can’t be sure he’s never pressured a sexual partner to go beyond where she wanted to. He’s admitted in interviews that his perspective is a limited white one.

But the gaps in this initial self-awareness quickly start to show. At one point, Leser references a letter he received after his Good Weekend feature was published, in which a woman thanks him for the piece and explains how it opened her eyes to abuse she’d experienced in her own life. This, he says, is “what contributed most to the belief that I should try to write this book”. But would that woman not have felt even more understood had the first story she’d read about Me Too been written by a fellow survivor? Was the response the piece received not an indication of Good Weekend’s immense reach rather his personal storytelling prowess?

Self-aggrandisement isn’t Women, Men and The Whole Damn Thing’s only problem. Across the 300-page book Leser documents the history of male violence and female persecution from the days of Ancient Greece through to the Geoffrey Rush trial, the murder of Eurydice Dixon, Aziz Ansari and the viral New Yorker short story “Cat Person”. While Leser acknowledges the knottiness of these cases, he never offers any answers. As such, re-treading this ground so soon after it all happened feels pretty pointless. Who is this dossier of male awfulness for? What does it achieve?

It also presents him with the problem of trying to cover events that are still playing out in real time — like the implosion of babe.net, the website that published the Ansari allegations. The site’s downfall was only documented by Allison P. Davis on The Cut in June, which means Leser conspicuously doesn’t consider how the now-defunct publication’s inexperienced editors and shonky editorial policies led to them bumbling the story. Instead, he attributes the fallout from the piece to mostly being a difference of opinion between second- and fourth-wave feminists.

To be clear, this book is not a trainwreck. Leser makes no excuses for his gender and doesn’t shy away from the horror of sexual violence. This is not a book that comes rushing to the defence of men everywhere, but one that unreservedly admits their fuck-ups. Leser leaves the impression of a man coming to terms with the magnitude of terror men have wrought — a sorrow, he notes, “women have always carried”.

Still, I can’t help but feel that a female author would have been able to push past these obvious truths and into something more analytical.

The parts of the book that were most compelling were the all-too-short chapters on the rise of incel culture and how toxic masculinity damages boys from an early age. Perhaps a more useful approach for Leser would have been to focus on unravelling this and offering a road map on how men can help each other be better.

I’m not sure it’s a mark in his favour, but Leser’s authorship does spotlight the ongoing conversation of when and how men should step in to pick up this fight. I was working as an editor of pop culture website Junkee for part of Me Too’s fallout and, as each new development rolled in, I found myself, as the only female editor on staff at the time, tasked with the job of handling it as men were afraid of putting a foot wrong. I found it profoundly exhausting and re-traumatising to spend my days wading back into the trenches of a battle I had my own scars from. By the end of my time in that job I’d all but thrown up my hands and refused to touch it. I felt that someone who didn’t have a personal stake in it all — a man — could do it instead.

The question might not be whether men can write about Me Too, but who they are writing about it for. We are at the point where we need men to do the heavy lifting and minister to their own gender. It’s just not clear if that’s what Leser has set out to do, or if he’s simply parasailed in feeling chosen, as men so often do, to explain it all to the rest of us.

If you or someone you know is impacted by sexual assault or violence, call 1800RESPECT on 1800 737 732 or visit 1800RESPECT.org.au.

What place do men have in the Me Too movement? Send you comments to boss@crikey.com.au. Please include your full name.

As a male I’m scared to touch it for fear of offence, however I do believe males have a role in this debate.

I’ve remarked to male friends that I have no knowledge of any man who has ever been violent towards a woman, on a related issue, however I must have worked with hundreds, and must be working with a few now, statistically at least.

Equally, aspects of the me-too movement that concern me are not something I feel free to voice. Not complaining, just saying.

In the spirit of not presuming a label on someone how about we extend that convention to cis ? You wouldn’t call someone gay if they’d not come out. Call yourself cis and those who you know have labeled themselves such. For everyone extend the courtesy of restraint.

It’s great to see transgender people finally getting mainstream acceptance but it doesn’t mean right on busybodies can speak for others.

FFS why not just accept his “cisgendered” intentions to do some good and get over your indignation on behalf of womanhood? It’s not as if there is a danger of straight men taking over the debate.

Too many chips, too few shoulders.

It’s a puzzling choice that a rag of Crikey’s stature would get a jobbing semi-literate emoter to rehash the work of a professional writer. After all, this is Metoo, one of the biggest moments in women’s social history.

Still, I can’t wait for her rehash of someone else’s account of far less substantial matters for women in society such as suffrage, contraception, total war, consumer capitalism, colonialism, slavery, sex work, celebrity cooks, and selfies.