This week marks the beginning of mid-year exams for many university students and they will be met with more anxiety than usual after a semester of unprecedented disruption.

Much has been written about the government’s response (or lack thereof) to the higher education sector’s funding crisis and subsequent job cuts and pay deals. The hardship faced by its workforce has dismayed all who care for academia — especially students whose classroom experience is only as good as the (usually casual) tutor teaching them.

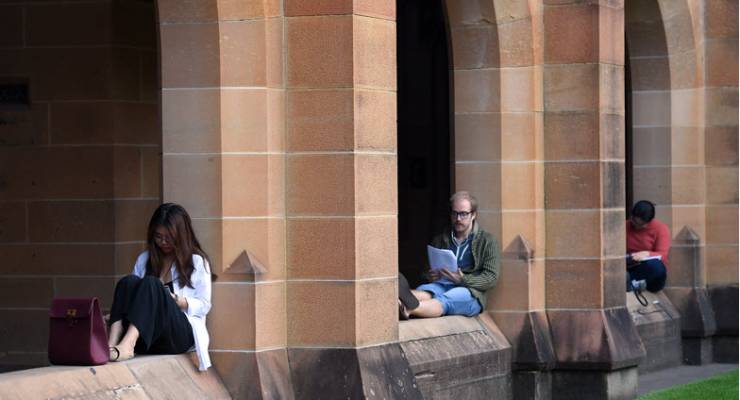

But less media attention has been given to students’ learning experience during the pandemic and the impact it may have on their futures. With campuses deserted and Zoom lessons often poorly approximating face-to-face tutelage, this may be the worst semester in history to be a tertiary student.

The pandemic ate my homework

Some unis adapted quickly and equitably to pandemic restrictions, enacting emergency policies such as extensions to census dates and assignments, grade amnesties and financial support. This required the co-operation of staff, administrators, students and their unions.

However, assessment has become a controversial flashpoint. Some universities instituted compensatory grading, allowing students to discount this semester’s marks from their final scores. Others are simply using a pass/fail system to adjust for isolation giving some students unprecedented time to study, while others have been distracted by extra work and caring duties.

But some universities have refused students’ pleas, proceeding with normal grading systems. This could slash otherwise high-achieving students’ grades, having a lifelong effect on their career and livelihood.

As well, while some unis have made at-home examinations “open book”, others have subjected students to controversial online tracking systems that record their movements and give assessors remote access to their personal computers to monitor for cheating. Students complain this invades their privacy and creates needless anxiety — stare out the window too long and the examiner may think you’re staring at your notes.

The most ambitious demand from student activists — that universities refund part of course fees to compensate for a lower quality of education — has gone largely unheeded. Only a handful are refunding the services and amenities fee, a fee for campus events and facilities that students can no longer use, while others just compensated international students early in semester to keep them enrolled.

Without another — more significant — government rescue package, administrators can hardly be blamed for clinging to their dwindling sources of revenue to stem the carnage.

Bachelor of economic utility

Beyond the pandemic, the government is gearing up for a focus on “skills” in education, appeasing employer groups’ calls to match graduate attributes to their needs. The immediate focus will be on reforming the TAFE system and online university short courses.

Providing students with relevant skills for the future economy is worthwhile, especially as students are anxious about their job prospects post-pandemic. But while TAFE is more explicitly industry-focused, university courses are not meant to be extended job training programs.

A university education is meant to give students a well-rounded appreciation of their field, so they understand its breadth and can engage with it critically. Graduates are meant to ask questions and propose ideas, not simply implement the bosses’ whims with maximal efficiency. Courses are meant to empower the next generation of knowledge workers, not simply serve up the job-ready human widgets many business leaders desire.

The “workforce bootcamp” view is particularly detrimental to arts and humanities departments that are less interested in prioritising narrow conceptions of job readiness over critical inquiries into their fields. We are already seeing cuts: several social science subjects are set to go at the University of Sydney despite protests saving some slated losses.

Students who have patiently sustained the sector throughout the crisis may soon find their academic choices limited and their education compromised.

Giving students a say

In an uncertain funding environment, governments and administrators may soon be tempted to adopt a top-down approach to cost cutting that ignores student suggestions about course content, assessment, fees and job pathways. But this would only exacerbate those issues.

Despite successive efforts by conservative governments to corporatise the sector and gut student unions, universities remain relatively democratic institutions to their profound benefit. Students and staff have designated seats on academic and corporate boards. Campus activists can still engage with administrators to promote the fair treatment of students.

As the first institutions that many young people can participate in and influence, student engagement with their universities teaches them valuable life skills beyond the classroom and fosters more open, responsive institutions.

What better way to prepare our young people for the workforce than involving them in corporate decision-making?

In respect of TAFE, the obvious necessary reform is to re-fund and reinvigorate the public TAFE system and systematically de-register the private shysters allegedly delivering VET.

Such as the sponsor of this piece?

Erm, is that “reforming the TAFE system”, or rebuilding the TAFE system to the model they so wilfully wrecked with their earlier ‘reforms’?

And I couldn’t agree more with Been Around’s comment above. All those Dodgy Brother Colleges operating more like labour hire companies providing cheap exploitable student labour to hospitality, convenience stores, servos etc, and being paid handsomely in taxpayers’ money to do it. Of course, that has suited the agenda of neoliberal governments and their donors so well, that it is hard to believe meaningful reform will come out of this.