The prime minister proposes to structure energy industry and infrastructure policy around the interests of the government’s big fossil fuel donors — Santos, Origin, Woodside — under the fiction that emissions-intensive gas is a “transition fuel” to an energy mix dominated by renewables.

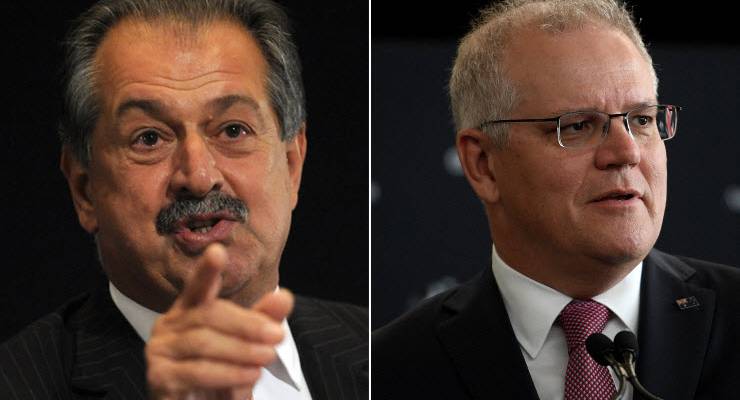

He’s doing so on the urgings of a “recovery commission” led by gas industry executives and advised by Andrew Liveris, a board member of world’s biggest greenhouse-gas emitter, Saudi Aramco, and a former Trump adviser.

Central to the policy, as spelt out by climate denialist Energy Minister Angus Taylor, is the government’s commitment that it will use its own energy infrastructure company, Snowy Hydro, to build a gas-fired power plant to cover an alleged shortfall in energy capacity after the ancient, creaking Liddell coal-fired plant in New South Wales closes.

The plant would be more than five times bigger than any identified shortfall in NSW.

This is disastrous from a climate perspective: Australia is on course to miss its unambitious Paris Agreement emissions reduction targets, but its government proposes to spend taxpayer money building emissions-intensive power plants when renewables and battery storage would do the job.

And it’s blatant corruption: its major corporate donors are literally writing policy they will directly benefit from.

The gas industry needs a lot of help if it is to remain viable long term. According to global energy giant BP’s 2020 Energy Outlook released yesterday, long-term world demand for coal, oil and natural gas is set to slow dramatically. For example, its central scenario forecast is for oil demand to not return to 2019 levels by 2025.

The share of fossil fuels (coal, oil and natural gas) has shrunk in the past as a percentage of overall energy mix, but total consumption has never contracted in absolute terms, which it will do under all three BP forecast scenarios.

That’s because, according to BP, the share of renewable energy is growing more quickly than any fuel ever seen in history.

But this kind of government help to an ailing industry is also disastrous from an investment perspective. The Australian Energy Council, which represents major electricity and gas businesses — i.e. the people who actually decide where and when to invest in energy infrastructure — says the government’s threats to intervene with its own spending “risks deterring the very investments the government is attempting to encourage”.

“The sector is struggling to make final investment decisions in an environment of ongoing policy uncertainty,” chief executive Sarah McNamara said.

And it comes on top of earlier bad policy: “The government’s earlier plan to underwrite new generation projects in the market also remains under consideration, and this too contributes to the ongoing uncertainty.

“There are no material reliability concerns that would warrant this kind of interventionist approach, and there are already mechanisms in place to address any shortfall identified.”

In case you’re thinking McNamara is some raving greenie or government critic, she’s a long-time Liberal staffer and former chief of staff to Ian Macfarlane when he was industry minister.

There’s another reason why Taylor’s plan will deter investment. It breaks the most fundamental rule of competition policy. If Taylor gets his way, the federal government will become a competitor in the energy market with its fossil-fuel donor-driven gas plant while still regulating energy markets.

It’s the core tenet of competition policy that governments shouldn’t both regulate and compete with an industry. As the Grattan Institute’s Tony Wood puts it, the government would be overseeing the market while it “has its own team in the field”.

How can investors make decisions confident that the regulatory playing field won’t be tilted to suit the interests of the government’s energy provider and its fossil-fuel donors?

Australia is not in a position to casually deter investment: business investment has collapsed under Scott Morrison.

It peaked in the December 2018 quarter and has been declining ever since. In the last quarter of 2019, before COVID-19 struck, it was back to levels last seen in 2010, propped up only by steady — though not rising — mining investment.

Private infrastructure investment in December 2019 fell to its lowest level since 2006, before the last mining boom.

Between the 2019 budget and last year’s MYEFO, the government was forced to write down its non-mining investment forecast for 2019-20 from 5.5% growth to 2% growth.

Energy infrastructure investment has been hit particularly hard: in 2019, utility-scale renewable investment fell more than 50%.

That’s the sign of a supposedly Liberal, business-friendly government failing in its core self-proclaimed strength of driving investment, all in the name of looking after its mates.

There’s another name for that: crony capitalism.

So much of what is wrong with politics and public policy can be linked to the stench of political donations.

I’m not even sure that its political donations. I think that it is more a moral certainty about the righteousness of the tribal cause.

The problem with Australian politics is the very stupid people who consistently vote conservative, I understand completely why the wealthy do, its in their interest, but why workers, families, the unemployed or pensioners do is a complete mystery.

So they can feel safe in their beds at night, presumably.

how true, we will end up worse than the USA

On the bright side, it’s only another announcement from a government short on action on its announcements, and the rationale is mostly to scratch political itches and hopefully cause Labor to stumble again.

Despite the rhetoric on cheap gas, the reality is that the proposed source of the gas is the Santos Narrabri project, as yet unapproved. Any approval for that is contingent on the construction of the missing pipelines and that is a fair way off and will also face serious opposition from landholders and the public. And Narrabri gas is not cheap gas, and even likely expansion of the drilling to the north and west won’t change that.

New generation based on expensive fuel that is needed for only a relatively short period over summer can only work to drive up energy prices or burn huge amounts of taxpayers’ money.

Oh, yes. Narrabri… drilling in the Pilliga State Forest.

Barnaby Joyce is up to his eyeballs in that scam. Before ditching his wife and kids to shack up with Vicki Campion, Barnaby bought a farm next to the forest. In 2017, he was being pressured to sell it due to an alleged conflict of interest around CSG [1]. After he started his sordid affair, his Chief of Staff Di Hallam, said to be disgusted, was given a plum job at Inland Rail [2, 3], and the route for a proposed railway line that would allow Santos to ship its crap out of Pilliga was changed to run right by his property [4]. If it ever got built, he’d be compensated… if he hasn’t sold it (and I haven’t yet found out).

But, hey, maybe it’s all a coincidence.

References:

How else is Scotty From Marketing going to keep those donations rolling in, if he doesn’t legislate in favour of those donor interests?

If they go broke there goes Scotty’s Coalition’s “Rivers of 30 pcs of silver”.

It’s called “Looking after your own self-interest”?

But he risks putting them all off if there is no investment certainty, klews. Sure he can fool the Australian public – especially those who voted LNP, that’s easy – but he will never pull one over the eyes of those canny investors. This is what i don’t understand (presumably because I don’t understand Marketing). How can Smirko hold the line that he has all the answers against those of his own tribe?

This is a good time to put in place renewable energy systems – but what does the LNP government do? Go with a fossil fuel that will become a stranded asset.

So-called “Energy Policy” has been a total failure for 10 years. Why would we think this version would be any better?

What policy? There isn’t one.