Mike Pezzullo is worried about the apocalypse. In a speech at the Australian National University last night, the powerful Home Affairs boss outlined his vision of the various events which could end civilisation as we know it.

A year ago, few would have seen a global pandemic coming. Now Pezzullo warns we should start thinking about other security threats, like pandemics, which could come from nowhere and dramatically alter the course of modern life as we know it.

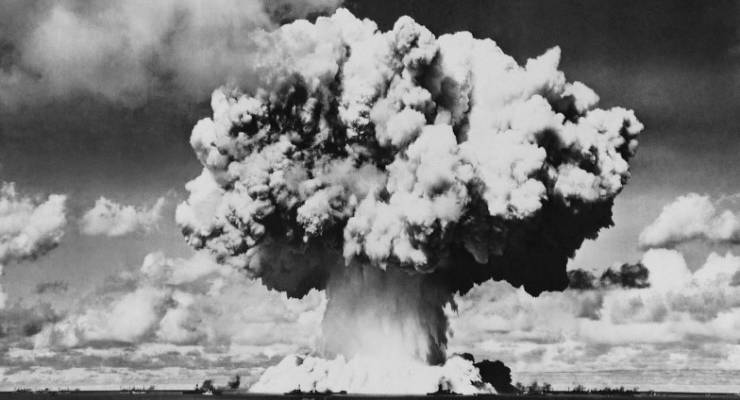

Sure there’s climate change and extreme weather events but Pezzullo wants us to worry about other stuff straight out of the realm of science fiction: super-volcanic eruptions blocking out the sun; a powerful geomagnetic storm rendering all electronic technology obsolete; a crippling cyber-attack sending us spiralling offline; the threat (seriously) of terminator-like AI; an asteroid hitting Earth; a nuclear apocalypse.

What are the odds of these apocalyptic visions ever being reality? Turns out, it’s pretty hard to say.

We started out by going to the bookies to see if anybody had run the numbers on the world ending. Turns out nobody would touch it — a market on the apocalypse was simply too crass even for betting companies.

So we asked University of Technology Sydney mathematician Stephen Woodcock about how one might go about predicting the scenarios. The answer really depends on what you’re trying to predict.

“There is a difference between events which are naturally occurring — pandemics, earthquakes, solar flares which have happened and will happen again — and the idea of the entirely man-made scenario,” Woodcock says.

With earthquakes and volcanoes, there were years of seismic data and early warning systems, he said. And pandemics tend to happen once in a century so there would be another in the future.

But when it came to human-made events like a nuclear war or a hostile AI takeover, guestimating was a fool’s game, he said.

“I don’t believe that anybody could give figures within orders of magnitude — you could be hundreds of thousands out,” Woodcock says. “You could obviously guess, but you’re making a whole suite of assumptions.”

The key reason it was so hard to figure out the odds was because, unlike natural phenomena, there’s no precedent for them, or any understanding of what the human response would be.

Put another way, to model the likelihood and impact of a future nuclear war, the best input we could get would be … an earlier nuclear war.

So, as terrifying as Pezzullo’s bolder warnings are it might be some relief that trying to work out when they’ll happen is pure guesswork.

It would have been good if you could have quoted some sections of the speech in context so we could understand his point but it sounds like Pezzullo should be removed from office and assessed to see if he’s right person to be running such a sensitive area.

To have someone in his position going to the public with a smorgasbord of threats no-one can control or influence seems worrying to say the least.

Did he wind up his speech by saying ‘and this is why we need collect more data on our own citizens and hand it over to the US to keep us all safe’ ?

Anything to take attention away from his side of politics and their total failure in regards to the climate

Right on Franky. Did Pezzullo approach ANU for him to deliver an apocalyptic speech or, did ANU seek out Pezzullo and he chose topic? If latter, what was Pezzullo’s objective? If ANU chose topic what the hell was their intent? Whatever the case one might assume most likely ANU approached ‘Spud’ and he flicked- passed the opportunity to further threaten citizens? No matter . . . neither topic, Presenter, or weird collection of academics present to hear their proposed demise, actually had the guts to address a true apocalyptic topic. The reality that global climate change already impacting and in everyones face? Yet still denied by LNP Ministers of the Crown and their Dept. Heads???

I don’t think anyone in their right mind would deny climate change. But It’s interesting that many volcanologists blame volcanic activity on climate change. I guess it stands to reason that even a minimal volcanic eruption alters the weather system within it’s own immediate vicinity. Now apply that over the many volcanic eruptions across the planet over the last 10-20 years and there is certainly considerable logic to the argument.

I am ready for you, Franky. let it rip.

Would the “many volcanologists” be like, or even the same sock puppets as, your previous “thousands of epidemiologists” who pooh-pooh covid?

FFS. Leaving aside the miserable tautology – pandemic is global by definition – there were endless warnings by just about every competent authority that a pandemic is inevitable in the near future; the only doubt was exactly when. Might as well say few would expect a cyclone coming to Australia this summer.

And people keep repeating the falsehood that pandemics only happen once a century – with population growth, global warming, habitat destruction, resource depletion and biodiversity loss, we could well face a fresh pandemic every decade until our numbers are severely whittled down. And bitter wars may add to the fun.

Pezullo is a self-serving ass who should do his job properly or get out.

Yeah,those blasted “once in 100/1,000” year events seem to occur with somewhat greater frequency lately, especially this century.

Fair mind, you forgot rampant international travel, which wasn’t around in 1918. Once a century before ubiquitous international travel, perhaps thatcomes down to once or twice a lifetime. I suspect I may be around for the next one.

How about he and his mates start looking at highly probable catastrophes caused by climate change.

I don’t know why Pezzullo bothers to fret and prognosticate about future crises because they have form for either getting predictions wrong or doing sfa when a crisis does happen. Both he and Dutton refused to even acknowledge let alone prepare for global warming, even as it was burning the country down around them last summer. On the other hand, when inescapably confronted by a catastrophic pandemic which serious experts had been warning about for years but to no avail, the deadly duo have proven to be ineffectual to the point of invisibility. Maybe they should just stick to what they are good at – tormenting refugees.