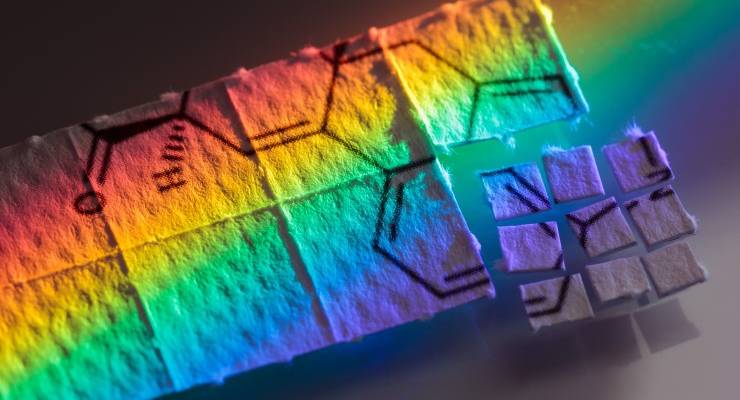

Once confined to raves, doofs and white guys with dreads, psychedelics are increasingly being recognised as a brave new treatment for chronic incurable mental illness.

Over the past decade there has been a groundswell of research into the potential of psychedelics to treat incurable mental illness. There’s growing evidence that MDMA and psilocybin can have positive effects treating post-traumatic stress disorder.

In Australia, about 20% of the population has some form of mental illness. Prescriptions for anti-depressants have risen (sertraline is one of the top 10 most common medications in the country), as have concerns about their overuse, side-effects and effectiveness with some conditions.

Freeing up doctors to use psychedelics for some of their most unwell patients could be the beginning of a dramatic shift in how we treat mental illness. But as clinical trials progress around the world and in Australia, there’s plenty of division among the medical establishment about when and how they should be used.

Last week the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) delivered an interim decision rejecting an application to get psilocybin (the ingredient in magic mushrooms) and MDMA reclassified as controlled medical substances — making them easier for doctors to prescribe.

The peak body for psychiatrists — whose submission influenced the TGA’s scheduling decision — has come under fire for its conservative position on psychedelics.

College criticised

In a clinical memorandum published last year, the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP) stated its position on psychedelics as treatment: although important progress was being made, further research was needed before they could be clinically prescribed.

Since the TGA ruling, there’s been more scrutiny of the RANZCP’s approach. A critique by researchers from Mind Medicine Australia (the group behind the reclassification push) and universities around the country slammed its paper for containing “referencing errors, misinformation, irrelevant data, and incomplete research”.

“The RANZCP position of restrictive stance on using MDMA as part of therapy is based on incomplete analysis and misinterpreted information,” it said.

And this week The Australian reported that several psychiatrists had savaged the paper for misrepresentations and perpetuating stigma.

Tania de Jong, executive director of Mind Medicine Australia told Crikey the College’s memorandum contained numerous errors, and used prejudicial language around psychedelics.

“They should also be transparent about who the authors are and what their relationships are to pharmaceutical companies ,” she said.

But psychiatrist Nigel Strauss, who wrote a submission in favour of rescheduling subject to stringent prescribing rules and who has been involved with all current clinical trials of psychedelics in Australia, says the college’s conservative position is understandable.

“I think the whole concept of psychedelics still carries stigma, and I think that older psychiatrists are still reluctant to embrace this treatment, and that’s still very much an influence on the way people in the college see it,” Strauss said.

At the same time, the RANZCP’s approach is evolving. Clinical trials of psychedelics around the world have forced establishment medical bodies to take notice.

Psychologist Stephen Bright from Curtin University founded Psychedelic Research in Science and Medicine a decade ago and says the college was opposed to any research in this area. Now it’s slowly coming around.

Strauss also says that although the college hasn’t given his work the support he would have liked, he’s optimistic it will become more practically involved.

Approval is just a matter of time

With momentum growing it’s only a matter of time before changes reach an Australian medical establishment that’s long been behind the curve. Even so, Bright believes the application for the TGA to reclassify was premature.

“You don’t make an application to the TGA to approve a medicine until phase-three clinical trials have been completed,” he said.

And even if it had approved, the costs of getting access outside a research setting — about $20,000 when hospital fees are factored in — are prohibitive.

But de Jong says there are already avenues in place to ensure patients can get cost-effective, safe and equitable access to psychedelics while research continues. All we need is the TGA to get on board.

“We’ve secured the medicines through the suppliers in North America at an extremely cost-effective rate, which means they’ll be equitably available across Australia through the special access benefits scheme.”

What’s indisputable though, is that Australia is on the brink of a major paradigm shift, with community attitudes already softening on psychedelic treatment.

“When I was speaking with shock jocks even seven years ago, they and their callers could understand the difference between clinical MDMA and dropping ecstasy at a rave,” Bright said.

“If conservative listeners get it, surely the government will too.”

Strauss says he understands there will always be many — both in the general public and medical profession — who are uneasy about the use of psychedelics.

“The word ‘psychedelic’ is like god, money and sex,” he said. “People project all kinds of things on to it and you get all kinds of issues.”

“So I’m not surprised conflicts arise. We just all need to keep calm.”

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.