The Australian Secret Intelligence Service (ASIS) established a station in Santiago, Chile in 1971 at the request of the CIA, who were working to destabilise Salvador Allende’s socialist government ahead of the country’s military coup, newly declassified documents reveal.

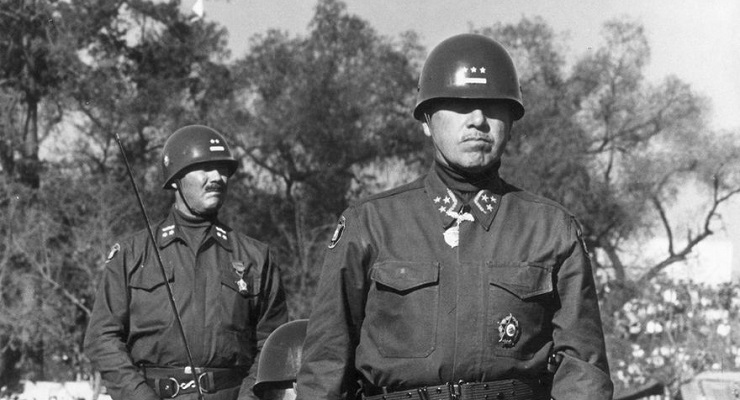

Limited information about the presence of Australian agents in Chile, and their role creating the conditions for General Augusto Pinochet’s military coup in 1973, have been in the public domain for decades.

But documents released today by the National Security Archive, a US-based research centre, provide the first official acknowledgement of ASIS’ role in Chile, and shed further light on former prime minister Gough Whitlam’s decision to close down the operation.

They’ve been unearthed through largely secret Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT) proceedings related to an attempt by UNSW Canberra professor Clinton Fernandes to declassify documents related to intelligence work in Chile ahead of the coup.

“This is the first ever official admission by the government that they set up a station in Chile, spied on Allende, and acted as a conduit between Pinochet and the CIA,” Fernandes said.

What the documents say

Much of the information released in the documents provides a rough everyday account of how the ASIS station in Chile was run. But they do give us an official picture of how the ASIS mission in Chile panned out, as well as Whitlam’s decision to end it.

In 1970, ASIS received approval from then-foreign minister Billy McMahon to open a station in Santiago, following “representations” from the CIA. This was just a month after Chile’s socialist president Salvador Allende had taken office, much to the fury of the Nixon administration in the US.

In mid-1971, a high-level Australian official (name redacted) questions whether the station’s opening should be deferred, noting the situation in Chile “has not deteriorated to the extent that was feared”, and that Allende “had been more moderate than expected”.

Within six months of the station’s opening, agents were having issues “settling in” in Santiago. For reasons that are redacted, the accommodation was “totally unsatisfactory”. Agents were still waiting for their cars to arrive. Their efficiency was being undermined by language barriers and the lack of a translation service — “a fluent understanding of Spanish in Santiago is a necessity”, the report says.

A year later, in December 1972, the Santiago station was still having “teething problems”. There had been several undisclosed incidents which were “cause for embarrassment”, undermining ASIS’ reputation, presumably with the Americans.

In early 1973, a recently elected Whitlam discovered the ASIS mission and ordered its winding up. The new documents confirm Whitlam’s decision was driven by fear of blowback.

In a series of memos, and correspondence with the Santiago station in early 1973, ASIS chief James Robertson says Whitlam felt uneasy about the intelligence presence in Chile and was frequently concerned about how he’d justify the mission to the public should details ever be revealed. Robertson says Whitlam described the decision as “most agonising”.

He also worried the US might interpret Australia’s withdrawal as “anti-American” — he wanted to make it clear he didn’t necessarily oppose US involvement in Chile, or support Allende.

“The prime minister was most concerned that CIA should not interpret this decision as being an unfriendly gesture towards the US in general or towards CIA in particular,” Robertson wrote.

In June 1973, three months before the coup, Robertson told Whitlam the station’s closure was complete. In July, accounts were being finalised and records destroyed.

What happens next

These documents make the picture of ASIS involvement in Chile a little clearer. But there’s still plenty that remains hidden. We know that even though ASIS formally closed the Santiago station in June 1973, at least one agent remained behind until a month after the coup.

While the documents hint at handling CIA-recruited Chilean assets, and some relationship with Langley, Virginia, details of what that work looked like is still hidden.

In June this year, Fernandes’ application to get those documents revealed by the National Archives was heard by the AAT. Most of the evidence tendered to oppose release of the documents was provided in secret, by ASIS officers operating under pseudonyms. The AAT is yet to make a final ruling.

In the meantime, Fernandes says there’s no reason the documents can’t be released straight away.

“I’d like to say the government should stop using national security as an alibi, and declassify the documents,” he said.

On this 48th anniversary of the ‘first’ 9/11, we ought to remember DrK’s lament -“I don’t see why we should let a country go socialist just because of the irresponsibility of its people“.

Of course, we/he/they did not allow it.

Intervention is never far away, as Whitlam discovered despite having kow-towed over Timor.

The CIA’s activities during 1954 in Guatemala were appalling and the 11/09/1973 action against Chile was a crime. Then came the Dismissal in 1975 when Marshall Greene (coup assistant) was the US Ambassador to Australia. Harold Wilson (UK) resigned suddenly in 1976 amongst rumors and the very early signs of illness. If your country has a democratically elected government with a social conscious the entire population is at risk.

Many more died as a result of the Chile 11 September incident. If you count the victmims of the Pinochet Junta and then add those who were victims of the USA/CIA sponsored Operation Condor run out of the right wing South American governments. It is estimsted thst at least 30,000 were victms of that programme, imprisoned, toryured or murdered.

Many of the perpetrators of those crimes being trained at the very nasrty School of The Ameiricas , Fort Benning, Georgia USA

Witness K and Bernard Keane are courageous heroes, and should be given honours. I am so disgusted with our government and their vicious attacks!