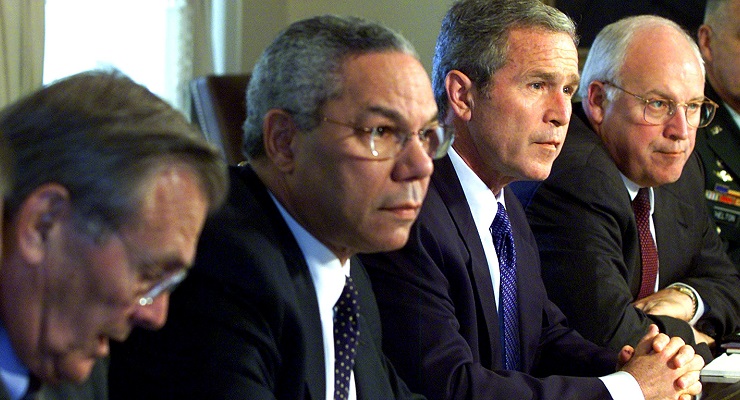

In the beginning, secretary of state Colin Powell was expected to be the star of the George W Bush administration. Judging from polls, the former joint chiefs of staff chairman and victorious Gulf War strategist was more popular than Bush, and he might have been president himself. Powell could silence a room just by clearing his throat — and he would present the judicious view in every cabinet meeting.

Powell, who died Monday at age 84, was heir to a treasured tradition of pragmatic internationalism harking back to his hero George C Marshall, another ex-general who became America’s top diplomat; Henry Stimson (secretary of state under Herbert Hoover and secretary of war under Franklin D Roosevelt); and Dean Acheson, Harry Truman’s secretary of state.

Powell added his own strategic embellishment to this tradition. A cornerstone of what came to be known as the Powell Doctrine was that the use of US military force should be astringent in the extreme. It should be mobilized only with overwhelming numbers, in situations where victory was near-certain, and where the exit strategy was clear. Powell also believed that the support of US allies was critical.

As we know, this did not become the view — or the policy — of the Bush administration. Bush went in virtually the opposite direction, unilaterally invading Iraq after 9/11 on concocted evidence (Powell’s worst moment in public life was presenting this evidence to the United Nations in 2003) with insufficient planning and no exit strategy in sight. The Powell Doctrine was also absent from 20 years of muddling through in Afghanistan, where there was no sense of what victory would look like.

“We could have avoided the expenditure of over $2 trillion dollars, the loss of the lives of more than 2300 US servicemen, as well as the tragic and humiliating disaster that is unfolding in Afghanistan if we had applied the Powell Doctrine 20 years ago,” Richard J Pierce Jr, a George Washington University scholar, wrote in the Hill in August.

According to Seth Jones, a military expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, most of the Powell Doctrine “appears to be relevant today, including the list of questions that any US policymaker needs to ask before deciding on military action”. Still, Jones said a revived Powell Doctrine will not be sufficient by itself. “The rules tell us whether or not to use force, not what happens over the course of a conflict,” he said.

The Powell Doctrine was born partly in Powell’s Vietnam experience. He did two tours, and as he wrote in his 1995 memoir: “Many of my generation, the career captains, majors, and lieutenant colonels seasoned in that war, vowed that when our turn came to call the shots, we would not quietly acquiesce in halfhearted warfare for half-baked reasons that the American people could not understand or support.”

Indeed, it was striking during the run-up to the 2003 Iraq invasion that the debate over whether to launch a “preemptive” war tended to break down along the lines of those who had fought in Vietnam and those who had not.

Among the biggest skeptics were Powell; retired Marine General Anthony Zinni, the former head of US Central Command; and then-senator Chuck Hagel, another Vietnam veteran. As Zinni, speaking for many of his former colleagues in the military brass, said in a speech in August 2002, “It might be interesting to wonder why all the generals see it the same way and all those that never fired a shot in anger and [are] really hellbent to go to war see it a different way.”

But as the Bush administration pushed its plans for the Iraq War forward, the Pentagon also made short shrift of the lessons of Vietnam.

It is true that almost none of the Bush administration hawks who pushed hardest for the Iraq War had served in Vietnam. Bush served in the National Guard at home, vice-president Dick Cheney got five draft deferments, and defense secretary Donald Rumsfeld did a stint in the Navy in the 1950s, getting out before the Vietnam War. Their ultimate goal was to leave the cloud of Vietnam behind, as Rumsfeld made clear during his confirmation hearings in early 2001.

“We want to be so powerful and so forward-looking that it is clear to others that they ought not to be damaging their neighbors when it affects our interests and they ought not to be doing things that are imposing threats and dangers to us,” Rumsfeld said. He was “trying to … beat back the attitudes of the Vietnam generation that was focused on American imperfection and limitations”, former secretary of state Henry Kissinger told Newsweek in 2002.

Now, however, we seem to be back to Powellian astringency, which itself is part of a historical cycle. Cold War hubris led the United States into Vietnam, and that in turn led to a generation of hesitation by chastened policymakers over the use of America’s so-called hard power. The Bush administration’s eagerness to reassert that power — and rebuff Powell — emerged largely as a hopeful corrective to that self-criticism.

Today, a new generation of US policymakers find themselves chastened not by “Vietnam Syndrome” but by what might be called “Iraqistan Syndrome” — a portmanteau term encompassing the twin quagmires of Iran and Afghanistan. And Powell may well be remembered most of all for his warning about the mess before it was made. His most succinct summation of the Powell Doctrine was what he called the “Pottery Barn” rule: “You break it, you own it.”

He bought in and enabled the IRAQ fake WMD conspiracy. Not an honest broker as he pretended to be.

This, with Bernard’s piece, constitutes a really well considered Powell obit.