The end of the parliamentary year is often ragged. Sometimes for oppositions. More often for governments. Everyone’s at the end of their rope. Governments are often keen to push slabs of legislation through, even if they’re being frustrated by the Senate. If there’s an election in the offing, it’s even worse, with backbenchers tempted to grab themselves some limelight and crossbenchers less inclined to cooperate.

Of course there’s traditionally a last-minute bout of well-wishing, seasons greetings and thank-yous to staff exchanged between MPs of all sides, but that seems to look more and more farcical each year. Scott Morrison yesterday used his to reel off his achievements during the year, then chip Labor about its “coalition” with the Greens.

After the Jenkins report released earlier in the week, it’s hard to take the thanks expressed to staff by any side particularly seriously. The abuse, harassment and exploitation of staff remains a huge problem for politics, along with the culture of entitlement and non-accountability that it partly derives from.

But for Scott Morrison, the end of 2021 was particularly ragged — worse even than the chaotic end of 2018, when his government was in minority. Notionally, Scott Morrison isn’t leading a minority government, but effectively he is, because so rampant is the indiscipline in his ranks that he can’t be sure his own troops will vote for his legislation, let alone convince the crossbench to pass it in the Senate.

Religious discrimination bit the dust after barely an hour of debate, shuffled off into a committee. Even the Christian fundamentalists are abandoning the bill. Class action curbs hit the fence, despite Zali Steggall backing them in the House. Voter ID was dumped altogether, a racist bill condemned to the garbage can it belongs in.

The government can’t pass its legislative agenda — but have a look at that agenda. Every one of those bills is a purely confected issue. There is no discrimination against religion in Australia. Curbs on class actions are intended to protect the government’s donors and supporters within board director ranks, not address a real issue. There is no problem of voting fraud in Australia (or in America, for that matter).

The government has no actual agenda addressing issues of substance — not on climate, not on wage stagnation, not on housing affordability, not on higher education, not even on defence, where the year has been marked by a major step backward in procurement of our next generation of submarines.

No wonder the government wants only a handful of sitting days in the first half of next year — it has no legislative agenda to pursue, even if it could be sure its own backbench would support it.

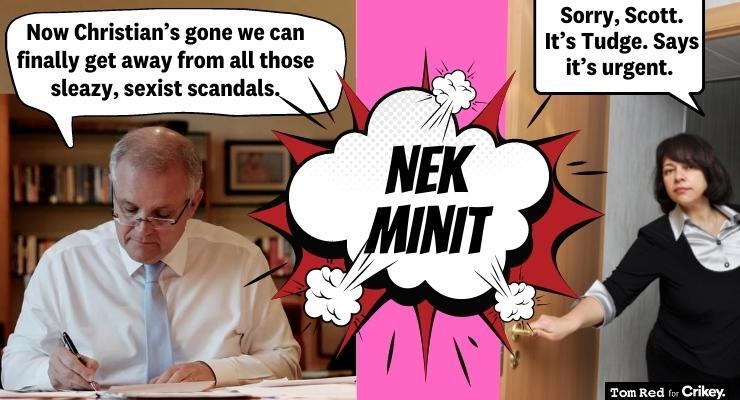

As quickly as the government was losing votes, it was losing ministers and ex-ministers. Couldabeen contenders Hunt and Porter going. And then the shock: Alan Tudge stood aside pending an investigation into allegations of abuse in his relationship with Rachelle Miller (allegations he rejects). The shock wasn’t that a man was alleged to have engaged in abuse of a woman with whom he was having a relationship, but that Scott Morrison thought the matter was politically damaging enough that he had to take action, even if the inquiry led by Vivienne Thom drags on into next year.

At least Morrison demonstrated some capacity to learn over the course of the year. The parliamentary year really began with Brittany Higgins’ remarkably brave decision to speak out about the alleged sexual assault she says she endured, and her treatment by the government thereafter. It ended with Rachelle Miller showing extraordinary courage — the kind politicians love to talk about but so rarely display — in speaking about what she says occurred in her relationship with Tudge.

Morrison’s grotesque mishandling of the Higgins matter — including some gutless staffers in his office backgrounding anonymously against her partner — did not repeat after Miller’s media conference; instead, Tudge was stood aside and an inquiry ordered.

If Morrison had been wise enough to do that with Christian Porter, the man would likely still be attorney-general.

In other ways, however, Morrison has learnt nothing. His response to the Jenkins report was wholly underwhelming, suggesting he still really has no grasp of the extent of the abuse of power going on right across Parliament. It’s always about the announcement with Morrison, never the substance. Part of his problems with his own backbench is that no one trusts him anymore; that they know Morrison’s commitments and promises to them are only as good as the next press conference; that his spin and words need to be ignored and action demanded instead.

No agenda, and no backbench support to pursue one. No substance. No leadership. And no trust.

Has Morrison learnt anything from his no good, very bad year? Let us know your thoughts by writing to letters@crikey.com.au. Please include your full name if you would like to be considered for publication in Crikey’s Your Say column. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity.

Dont forget Marrison does actually have an agenda. Its a hidden agenda so its easy to miss. His plan is to serve out his time and then retire with a massive Prime miniaterial pension plus perks. Thats the minimum. The plan also includes the goal of accumulating enough obligations among the corrupt business community for favourable legislation passed or left in place that they reward him with sufficient directorships, speaking engagements etc that he can pull an annual 7 figure income on top of the pension. Thats the plan. Its the only way I can explain what he is up to.

Dunno about the speaking engagements possibility. I know that he could talk under wet concrete but his word salads are totally incomprehensible to ordinary speakers of English. Will corporate interests really pay much to hear such sludge?

Perhaps he’s speaking in tongues.

He’d make sense if he were speaking in tongues.

Yes

Well, Abbott is horrid as speaker and yet some had paid to hear him. You never know…

It takes a very particular and nasty mindset to appreciate an Abbott speech, so there would be a similar subset of people ugly or deluded enough to pay for Smirko speeches.

Speaking engagements? Who would want to listen to Scott unless they had to, let alone pay for it?

He’ll be going to ‘Tongues’ – to be speaking in …….?

Who would want to listen to Abbott, and pay for it? But they did.

An entire budget (is that the collective term?) of RWNJ ginger groups and worse?

So far he’s spoken to Britons who regard Brexit as insufficient cleavage who are allied to Magyars think the EU a rerun as the paprika squeezed between the meat of the secular West, the religious North and the alien East who are equally keen on the Eastern Orthodox Renaissance, yay even unto Constantinople!

No pension until 60 tho?

PM receives his pension from when he loses his job.

Thanks Bernard. What a total embarrassment and disappointment (Yes, that word again.) our wannabe Prime Minister is. He holds the position but does nothing and that makes him a wannabe without substance in my eyes. He is certainly no kind of a leader.

“The government has no actual agenda addressing issues of substance…” This has been the case since Tony Abbott’s first fumbling cabinet meetings without any agenda and on into Turnbull’s front bench locked into inactivity by right wing nut jobs and followed up by Scott the Ever-Unready without an idea in his head.

We need change and there is no time to lose before Dutton orders our Defence Force to attack China.

Well Nigel, you may not have missed the mark about “our” defence minister …he has after all, been trying to terrify the country with grand statements about Chinese Missiles that could be aimed and presumably fired at Australian cities …”including Hobart”.

His statements were, obviously not taken kindly by the Chinese government.

Was it Ms Wong who said, “Mr Dutton has just auditioned for the job of PM”?

That statement terrified me more than Mr Dutton’s.

Of course he laughingly denied he was doing so (auditioning as next PM)..saying instead that Morrison would be PM until 2040.

Which person is the lesser of two evils?

Yeah. Nah.

Neither actually!

I do wish Ms Wong stood for the “top” job if Labor was ever elected … sadly it won’t be in my lifetime.

Mr. Dutton is not clever enough to be PM and neither is Scott, as is shown on a daily basis as Australia lurches from one cock-up to the next. It’s a wonder that we are still here at all.

Your last statement is rubbish! Have you looked at the polls lately???

ANY Labor government could not possibly be worse than what we have at present…and Mr Albanese is leading a very good team!!

I agree- she is an extraordinary human being. Contrasting she and Tanya Plibersek with ScoMo Dutton and B Joyce is enough to make one weep. How can these men be our voice on international stages. Truly embarrassing.

Let’s not forget Ms K Keneally.

I was ready to press + but for the last throw away sentence, yeah, nah, Dutton is not that silly.

He’s already been briefed that our signals directorate already struggles to contain foreign goon squads of cyber hackers.

Just through weight of numbers, we’d be toast.

As for military conflict, that’s just insanity, even if it’s in the Spratly’s, just no.

Dutton like small vulnerable targets where he has total control.

There is no evidence of intelligence where Mr. Dutton is concerned, though he has exhibited low animal cunning on a number of occasions.

But we haven’t got our toothpicks yet we will get rolled

When one reflects on the list of things he wants but can’t get through they have a common theme. Removing accountability or responsibility. The religious bill, freedom to continue discrimination, the class action bill, protect board directors etc., the integrity commission, protect politicians from investigation. The only one that increased responsibility was the voter id, with its burden falling fair and square on the marginalised. Even in what he can’t do his “agenda” is quite clear.

Morrison? Always good to end with a joke?

It’s gotta take buckets of gall for anyone, in Coalition with Cousin Jethro and Ellie-May McKenzie’s Beverly Hillbillies, to chip anyone else about their “coalition” with a fourth party? ….. Either that or it’d take a complete lack of self-awareness and shame?

Ellie-May from the actual Hillbillies deserves a little more respect she was not manipulative or coercive in any malicious way. Jed handled it well and while Jethro frothed it was all a way higher standard than this incumbent government

Kept a low profile. Never saw much of Ellie-May …. made me suspicious of what she was doing away from the prying eyes of the camera….jugglin’ pork-barrels out back, I always suspected. .

Hmmm. Why has the Beatles’ song ‘Nowhere Man’ suddenly come to mind, I wonder?

Nowhere Man (Remastered 2009) – YouTube

Now you’ve ruined it for me…that was one of my favourite Beatle songs!

I suggest that Labor play this every time they want to have a go at Morrison during the coming election campaign.

What about “TaxMan’? That IS classic!

Except that is a calumny on progressive taxation –

“There’s one for you, nineteen for me” referring to the component parts of a pound (which cannot be named for fear of tripping the madBot).

The top rates in such a system apply only to the amounts above each level, not the whole amount as is still the constant claim of ratbag rightists.