It’s not even close to the longest campaign in recent history, but Scott Morrison is counting on using every day of the six weeks until polling day to wear down Anthony Albanese’s lead.

That ostensibly defies the lesson of long campaigns, which is that over the course of them governments lose votes.

Bob Hawke’s 53-day campaign in 1984 saw a massive Labor lead evaporate and Andrew Peacock revel in the spotlight. Labor ended up losing seats, though it had a substantial buffer. In 2016, while lacking Hawke’s massive polling lead, Malcolm Turnbull was expected to cruise to victory over Bill Shorten over an eight-week campaign. He ended up losing 14 seats.

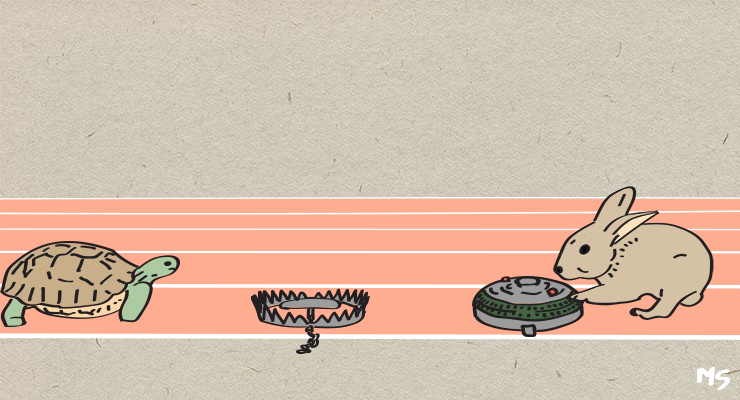

But Scott Morrison isn’t in government. Or at least, he won’t campaign as the government. He’ll enjoy all the benefits of being in government — being called “prime minister”, controlling the country’s finances so he can pork-barrel key seats — but as in 2019 he’ll be campaigning as opposition leader against Labor.

In 2019 Morrison campaigned as though it was Labor that was in government and needed its policies scrutinised, while he gave up any pretence that he was actually governing. He offered no agenda or vision, merely a series of scare campaigns about Labor policies and a daggy dad persona designed to appeal to disengaged voters.

Now he’ll take the same approach, offering nothing but pork-barrelling and bribes, while looking for any opportunity to frighten voters about Albanese and the ALP. It was hugely successful in 2019 and could be so again. Today’s Newspoll already shows Labor’s once-massive lead narrowing.

The strategy accords with Morrison’s own style of “governing”, which is to do as little as possible and avoid blame when anything goes wrong, and use announcements and media releases as substitutes for actual policy. Morrison has used his leadership to craft a new kind of prime ministership — in which the incumbent is in power but mysteriously floats above all responsibility, a kind of powerful passivity; Morrison can never be held to account, but everyone else must be, particularly Labor.

He’s been helped in this by a press gallery that has been reluctant to do the hard work of holding him accountable — which overlooked his routine lying until Crikey began calling it out, which overlooked his climate inaction and even pretended he had a climate policy, which overlooked his refusal to accept even the most basic standards of anti-corruption safeguards, which ignored his dramatic increase in the size of government, fuelled by a generational debt.

Albanese’s Labor, of course, has declined to present the same rich target of policies as Bill Shorten and Chris Bowen did in 2019. It wants to keep the focus entirely on Morrison, rather than on Labor policies. Having happily been a vehicle for scare campaigns against Labor’s proposed agenda in that campaign, much of the press gallery is now expressing its frustration at Labor’s refusal to serve itself up on a plate again. As a consequence, it is declaring that Albanese is “unknown” and has failed to convey who he really is, that voters don’t know him.

Paint a target on your back, the press gallery opens fire. Refuse to do so, you’re hiding and can’t be trusted. That’s despite John Howard offering virtually nothing by way of policy while heading to a landslide victory in 1996, except a few promises that, in government, became “non-core”.

Then again John Howard was a known quantity in 1996 — he’d been in Parliament for 22 years. Anthony Albanese has only been in Parliament for… 26 years. He first arrived during that Howard landslide. Whether the lessons from 1996 still apply will be one of the themes of this election campaign.

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.