Dear Mark,

Welcome aboard!

There’s much to do so I’ll cut straight to the chase.

Firstly, I urge you to be a minister for health, not just healthcare. The distinction is important. Health is more than the absence of disease. Healthcare is mostly concerned with treating illness. It has little to say about promoting health and avoiding illness unless it involves medical interventions (part of the problem is how we pay for care… but we’ll get to that).

I know everybody’s over the pandemic. But it is far from over. Please listen to experts and work with, not against, the states and territories on containing it.

We simply must invest more in promoting health and tackling “upstream” risk factors. We have a pedigree. Australia led the world in reducing tobacco use — a globally recognised great public health success despite a determined campaign from vested interests. We need strong leadership like that to meet emerging health challenges.

I’m sure you know that the most powerful determinants of health (and disease) are social and economic. Inequality is especially harmful. It reduces everyone’s health, not just those at the bottom. The government — your government — has the levers controlling many of the factors affecting our health: education, tax, housing, social services and welfare. I therefore hope you will promote health in all policies across the relevant portfolios and through the Council of Australian Governments (COAG).

Now let’s talk about what we call the health system but which in fact covers mainly medical care. To be honest, it’s a stretch to call it a system at all; it’s more like patchwork, a marble cake that’s increasingly struggling to address modern demands.

Some serious changes are needed to improve how the current arrangements work for patients and consumers as well as those for those who toil every day to deliver care.

Hospitals are expensive and at times dangerous places. We must do everything we can to keep patients out of them, and if not, to ensure that their stay is as short and as safe as possible. I concede that this is difficult under a funding model that rewards activity and I caution against simply throwing more money at public hospitals. Inflating the balloon won’t reduce the pressure.

While the states run our public hospitals, the Commonwealth is responsible for primary care. Rising levels of chronic disease mean that our GPs and allied health professionals are on the frontline in helping people manage their health problems and keep them out of hospital. It also gives them a landing pad after they leave acute care, freeing up beds faster and helping reduce wait times at the front door.

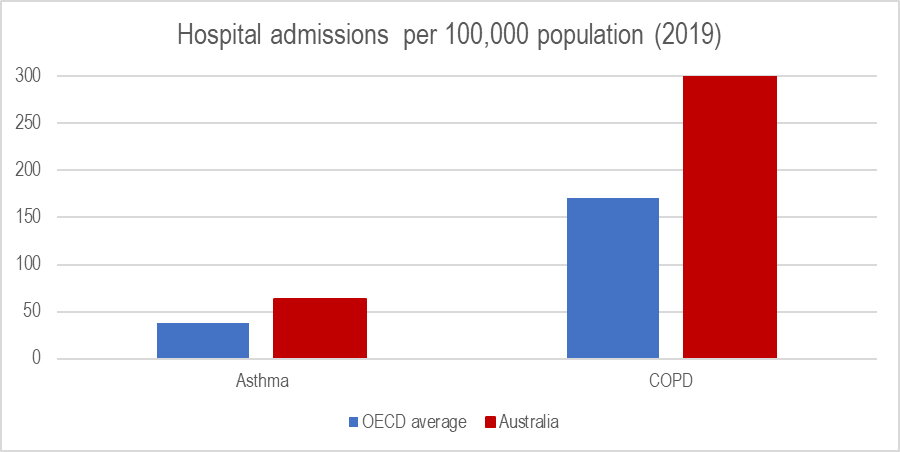

But we have a GP shortage in areas of greatest need (the inverse care law). Many patients don’t see their doctor because of high out-of-pocket costs (bulk billing data is a sham). Little wonder that compared to those living in other OECD countries, Australians are almost twice as likely to be admitted for respiratory conditions, most of which should be managed out of hospital.

You can help bolster primary care in several ways. In the long term, we need a discussion with our medical colleagues about changing the training, socialisation and culture of medicine to value generalists as highly as specialists.

But we also need to increase how much GPs earn. Among OECD countries that provide this data, Australia has the second-lowest GP income rates relative to their specialist colleagues. A career in general practice (a specialisation in its own right) should be a financially attractive option.

If we must have a fee-for-service model, at least we should structure it to reflect various levels of patient complexity. Providers must have an incentive to invest the time to help their most vulnerable patients. A good start would be to raise the Medicare rebate for general consultations. This should at least begin to improve access for our poorest (and sickest).

But at some point, we need to discuss ways to fund care that rewards value, not just volume, in general practice and hospitals. Perhaps we could try paying providers a lump sum per patient based on their level of health need (Gonski for health)? Or we could bundle payments for interventions like elective surgery to cover the entire care cycle, from diagnosis to rehab, rather than pay for each individual component as if the patient were a product on an assembly line.

Most Australians receive elective procedures in the private sector. “Private” healthcare in this country is a cosy arrangement between insurers and providers, all propped up by billions courtesy of the taxpayer each year. The truth is that private health diverts resources away from the public sector, rather than taking pressure off it. The result is a two-tiered arrangement where those who can afford it get care (sometimes excessive and unnecessary care) while those who can’t go without, languishing on waiting lists. Little wonder the industry is in a death spiral.

We can have a private sector, but it must be designed to serve consumers — not providers and insurers. Several things can be done. Stronger regulation on fees and charges, including better transparency and limits. Also, why not publish provider outcomes so that patients can assess the quality they’re getting for their money?

Please do press on with efforts to modernise the Medicare Benefits Schedule, which is full of items that are obsolete or do not reflect effective, high-value care. And maybe giving more say to health funds in how care is delivered could improve efficiency and value in the private sector.

Finally, please remember that health isn’t a commodity, and healthcare is fundamentally different to any other service or product. Market forces can play a role, but relinquishing it all to the invisible hand will simply ensure that we will pay more for worse health outcomes. For evidence, just look at the USA.

In fact, you need not look abroad at all. Australian aged care is a prime example of what happens when we leave it to the market with little regulation and oversight. It’s a complete mess, and a taskforce to implement the Royal Commission findings is needed as soon as possible. Perhaps we’ll leave dental care for another time…

Remember this: “There is nothing more difficult to plan, more doubtful of success, nor more dangerous to manage than a new system. For the initiator has the enmity of all who would profit by the preservation of the old institution and merely lukewarm defenders in those who gain by the new ones.”

Machiavelli said this, and he was spot on.

Don’t waste a day.

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.